Most of us spend much more time with digital media than we did a decade ago. But today’s teens have come of age with smartphones in their pockets. Compared to teens a couple of decades ago, the way they interact with traditional media like books and movies is fundamentally different.

My co-authors and I analyzed nationally representative surveys of over one million U.S. teens collected since 1976 and discovered an almost seismic shift in how teens are spending their free time.

Increasingly, books seem to be gathering dust.

It’s all about the screens

By 2016, the average 12th grader said they spent a staggering six hours a day texting, on social media, and online during their free time. And that’s just three activities; if other digital media activities were included, that estimate would surely rise.Teens didn’t always spend that much time with digital media. Online time has doubled since 2006, and social media use moved from a periodic activity to a daily one. By 2016, nearly nine out of 10 12th-grade girls said they visited social media sites every day.

Meanwhile, time spent playing video games rose from under an hour a day to an hour and a half on average. One out of 10 8th graders in 2016 spent 40 hours a week or more gaming – the time commitment of a full-time job.

With only so much time in the day, doesn’t something have to give?

Maybe not. Many scholars have insisted that time online does not displace time spent engaging with traditional media. Some people are just more interested in media and entertainment, they point out, so more of one type of media doesn’t necessarily mean less of the other.

However, that doesn’t tell us much about what happens across a whole cohort of people when time spent on digital media grows and grows. This is what large surveys conducted over the course of many years can tell us.

Movies and books go by the wayside

While 70 percent of 8th and 10th graders once went to the movies once a month or more, now only about half do. Going to the movies was equally popular from the late 1970s to the mid-2000s, suggesting that Blockbuster video and VCRs didn’t kill going to the movies.But after 2007 – when Netflix introduced its video streaming service – moviegoing began to lose its appeal. More and more, watching a movie became a solitary experience. This fits a larger pattern: In another analysis, we found that today’s teens go out with their friends considerably less than previous generations did.

But the trends in moviegoing pale in comparison to the largest change we found: An enormous decline in reading. In 1980, 60 percent of 12th graders said they read a book, newspaper or magazine every day that wasn’t assigned for school.

By 2016, only 16 percent did – a huge drop, even though the book, newspaper or magazine could be one read on a digital device (the survey question doesn’t specify format).

The number of 12th graders who said they had not read any books for pleasure in the last year nearly tripled, landing at one out of three by 2016. For iGen – the generation born since 1995 who has spent their entire adolescence with smartphones – books, newspapers and magazines have less and less of a presence in their daily lives.

Of course, teens are still reading. But they’re reading short texts and Instagram captions, not longform articles that explore deep themes and require critical thinking and reflection. Perhaps as a result, SAT reading scores in 2016 were the lowest they have ever been since record keeping began in 1972.

It doesn’t bode well for their transition to college, either. Imagine going from reading two-sentence captions to trying to read even five pages of an 800-page college textbook at one sitting. Reading and comprehending longer books and chapters takes practice, and teens aren’t getting that practice.

There was a study from the Pew Research Center a few years ago finding that young people actually read more books than older people. But that included books for school and didn’t control for age. When we look at pleasure reading across time, iGen is reading markedly less than previous generations.

The way forward

So should we wrest smartphones from iGen’s hands and replace them with paper books?Probably not: smartphones are teens’ main form of social communication.

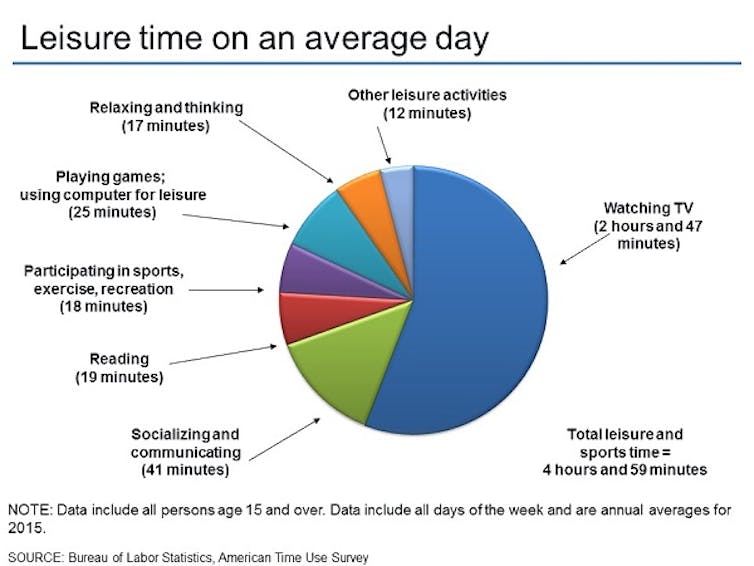

However, that doesn’t mean they need to be on them constantly. Data connecting excessive digital media time to mental health issues suggests a limit of two hours a day of free time spent with screens, a restriction that will also allow time for other activities – like going to the movies with friends or reading.

Of the trends we found, the pronounced decline in reading is likely to have the biggest negative impact. Reading books and longer articles is one of the best ways to learn how to think critically, understand complex issues and separate fact from fiction. It’s crucial for being an informed voter, an involved citizen, a successful college student and a productive employee.

If print starts to die, a lot will go with it.

Jean Twenge, Professor of Psychology, San Diego State University

This article was originally published on The Conversation.