One of the world’s most famous Christmas carols, “Silent Night,” celebrates its 200th anniversary this year.

Over the centuries, hundreds of Christmas carols have been composed. Many fall quickly into obscurity.

Not “Silent Night.”

Translated into at least 300 languages, designated by UNESCO as a treasured item of Intangible Cultural Heritage, and arranged in dozens of different musical styles, from heavy metal to gospel, “Silent Night” has become a perennial part of the Christmas soundscape.

Its origins – in a small Alpine town in the Austrian countryside – were far humbler.

As a musicologist who studies historical traditions of song, the story of “Silent Night” and its meteoric rise to worldwide fame has always fascinated me.

Fallout from war and famine

The song’s lyrics were originally written in German just after the end of the Napoleonic Wars by a young Austrian priest named Joseph Mohr.In the fall of 1816, Mohr’s congregation in the town of Mariapfarr was reeling. Twelve years of war had decimated the country’s political and social infrastructure. Meanwhile, the previous year – one historians would later dub “The Year Without a Summer” – had been catastrophically cold.

The eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora in 1815 had caused widespread climate change throughout Europe. Volcanic ash in the atmosphere caused almost continuous storms – even snow – in the midst of summer. Crops failed and there was widespread famine.

Mohr’s congregation was poverty-stricken, hungry and traumatized. So he crafted a set of six poetic verses to convey hope that there was still a God who cared.

“Silent night,” the German version states, “today all the power of fatherly love is poured out, and Jesus as brother embraces the peoples of the world.”

A fruitful collaboration

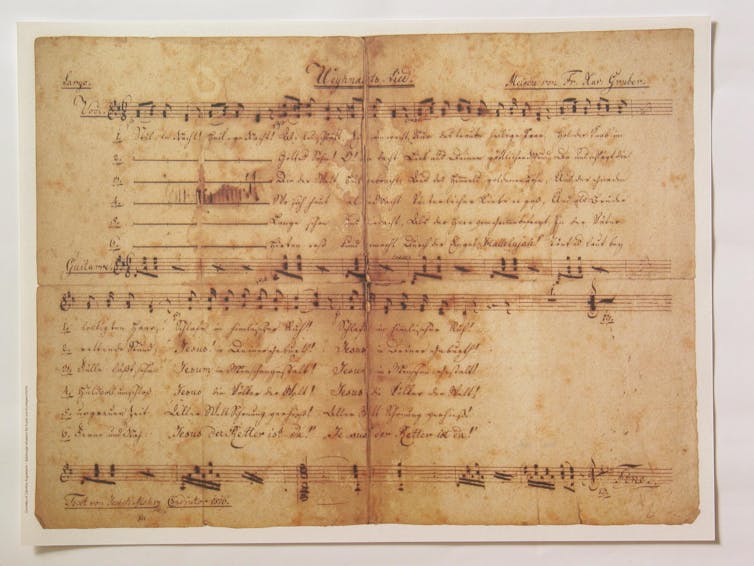

Mohr, a gifted violinist and guitarist, could have probably composed the music for his poem. But instead, he sought help from a friend.In 1817, Mohr transferred to the parish of St. Nicholas in the town of Oberndorf, just south of Salzburg. There, he asked his friend Franz Xaver Gruber, a local schoolteacher and organist, to write the music for the six verses.

On Christmas Eve, 1818, the two friends sang “Silent Night” together for the first time in front of Mohr’s congregation, with Mohr playing his guitar.

The song was apparently well-received by Mohr’s parishioners, most of whom worked as boat-builders and shippers in the salt trade that was central to the economy of the region.

The melody and harmonization of “Silent Night” is actually based on an Italian musical style called the “siciliana” that mimics the sound of water and rolling waves: two large rhythmic beats, split into three parts each.

In this way, Gruber’s music reflected the daily soundscape of Mohr’s congregation, who lived and worked along the Salzach River.

‘Silent Night’ goes global

But in order to become a worldwide phenomenon, “Silent Night” would need to resonate far beyond Oberndorf.According to a document written by Gruber in 1854, the song first became popular in the nearby Zillertal valley. From there, two traveling families of folk singers, the Strassers and the Rainers, included the tune in their shows. The song then became popular across Europe, and eventually in America, where the Rainers sang it on Wall Street in 1839.

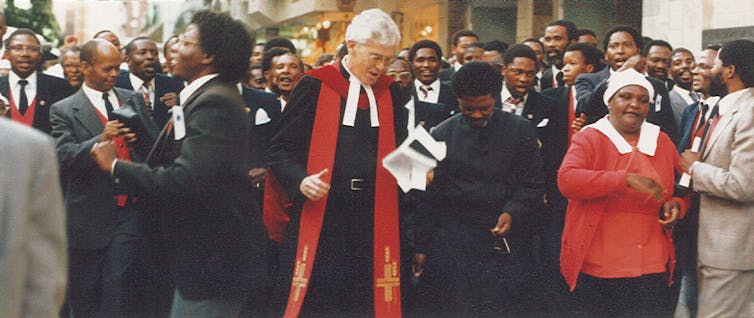

At the same time, German-speaking missionaries spread the song from Tibet to Alaska and translated it into local languages. By the mid-19th century, “Silent Night” had even made its way to subarctic Inuit communities along the Labrador coast, where it was translated into Inuktitut as “Unuak Opinak.”

The lyrics of “Silent Night” have always carried an important message for Christmas Eve observances in churches around the world. But the song’s lilting melody and peaceful lyrics also reminds us of a universal sense of grace that transcends Christianity and unites people across cultures and faiths.

Perhaps at no time in the song’s history was this message more important than during the Christmas Truce of 1914, when, at the height of World War I, German and British soldiers on the front lines in Flanders laid down their weapons on Christmas Eve and together sang “Silent Night.”

The song’s fundamental message of peace, even in the midst of suffering, has bridged cultures and generations. Great songs do this. They speak of hope in hard times and of beauty that arises from pain; they offer comfort and solace; and they are inherently human and infinitely adaptable.

So, happy anniversary, “Silent Night.” May your message continue to resonate across future generations.

Sarah Eyerly, Assistant Professor of Musicology and Director of the Early Music Program, Florida State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.