Is Crockett Johnson’s Harold, of “Harold and the Purple Crayon,” a child of color?

If you’ve bought any of the “Harold” books published in the past 25 years, or saw the new movie starring Zachary Levi as an adult Harold, your answer is probably “No.”

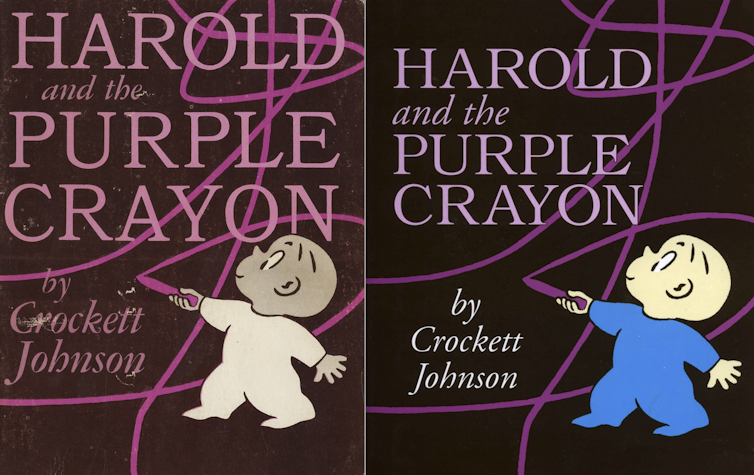

In 1998, HarperCollins relaunched the “Harold” books – seven picture books in which the title character, standing on a blank page, uses his purple crayon to draw the world and his adventures in it.

The physical copies of the new editions are larger, and the publisher modified the covers, changing the color of Harold’s jumper from white to blue and altering Harold’s original tan complexion to light peach – even though Harold remains tan within the pages of the books.

Their decision likely influenced the creators of the “Harold and the Purple Crayon” TV show, which aired on HBO from 2001 to 2002, to use similar colors for Harold’s skin tone, and probably prompted the creators of the new film to cast a white actor as Harold.

In other words, the light-skinned 1998 Harold has become the standard depiction.

Fifty years ago, when I was a little white boy, I, too, read Harold as white. When I saw the new covers in 1998, I didn’t think they had changed Harold’s race. Now, however, I’m not so sure.

As Johnson’s biographer and a scholar of children’s literature, I started to wonder about Harold’s race while researching “How to Draw the World: Harold and the Purple Crayon and the Making of a Children’s Classic,” which will be published in November 2024.

I discovered that not everyone has seen Harold as white – possibly, not even Johnson himself. When cartoonist Chris Ware, who’s also white, was a little boy, he read Harold as Black. When picture book creator Bryan Collier, who’s Black, was a boy, he both read Harold as Black and “imagined himself as Harold.”

They’re not the only ones.

So, is Harold Black? And what would it mean if he were?

Printing colors in the 1950s

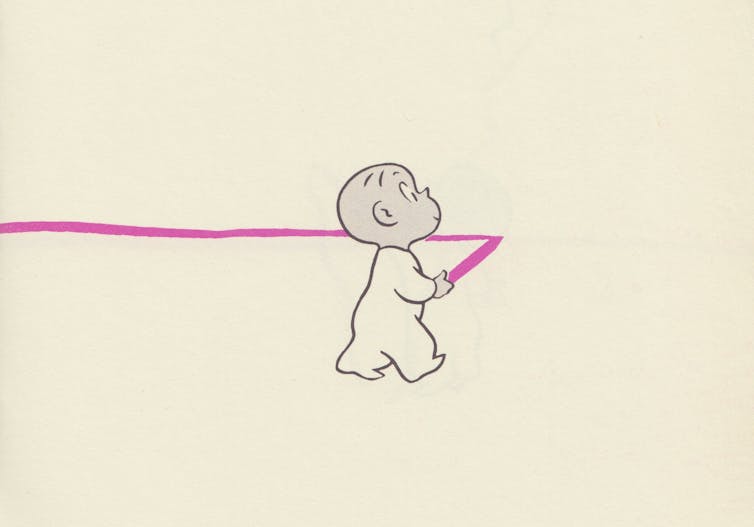

Unlike other picture books of the 1950s, which usually used three or four colors, “Harold and the Purple Crayon” used only two: brown and purple.

The offset color lithography printing process then used for picture books required that each color be added in its own phase: In the case of “Harold,” a purple phase and a brown phase.

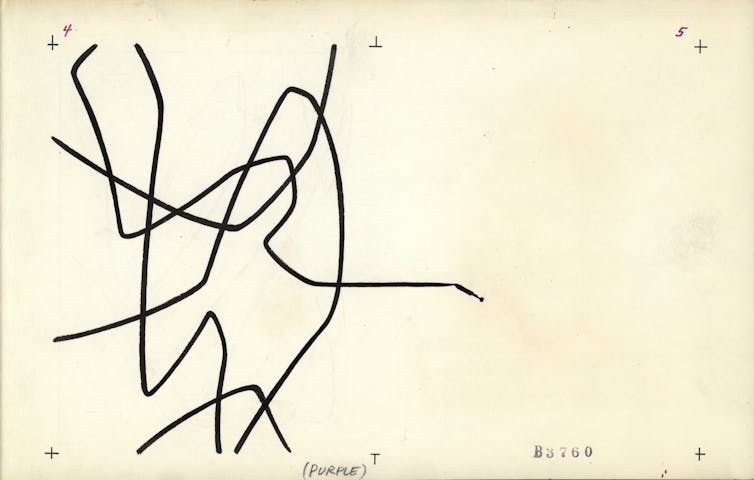

Johnson created two versions of each two-page spread. On one, he drew the path of the purple crayon, writing “PURPLE,” to specify that the black lines be printed in purple.

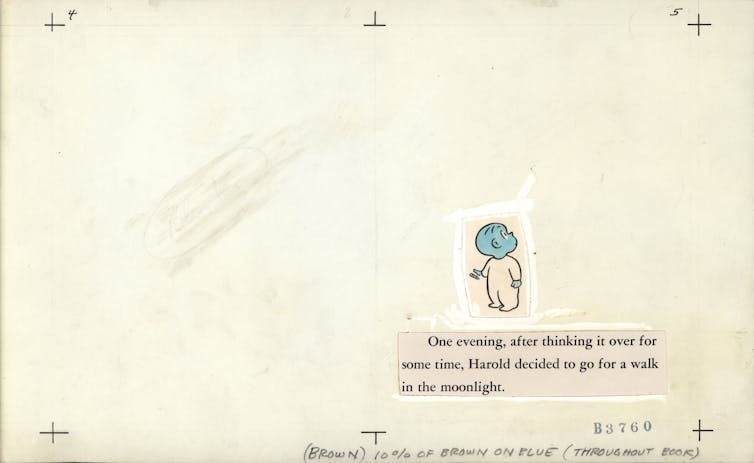

On the other sheet, he wrote “BROWN” for the outlines of Harold’s body and the text, each of which he had pasted on the sheet.

Finally, he painted a blue watercolor wash over Harold’s face and hands. And he wrote “10% OF BROWN ON BLUE” to indicate that, via a filter that screens out 90% of the brown, a light brown would be printed on top of the blue areas.

When, in two separate stages – one for purple, one for brown – the printer applied each of these colors, the final page would show a tan-complexioned boy, outlined in brown, drawing with a purple crayon.

Harold is literally a brown-skinned child. But skin color is not race. And it’s possible that Johnson was restricting himself to two colors to keep costs down.

However, as cartoonist and comics historian Mark Newgarden told me, using 10% brown to create “Caucasian ‘flesh’” is unusual. At the time, racially white skin would have been created with a magenta screen. Within Johnson’s two-color printing plan, Newgarden continued, “paper stock white and 10% of that purple (close to pink) are both visually closer to how Caucasian ‘flesh’ would typically be represented” in 1950s children’s books.

Brown, therefore, was a deliberate choice.

The rarity of using 10% brown suggests that, in making a child of color the central character of his Harold books, Crockett Johnson may have been at the vanguard of mainstream American children’s literature. He was creating a Black protagonist nine years before Ezra Jack Keats’ 1962 book “The Snowy Day,” which became the first title featuring a Black protagonist to win the Caldecott Medal, the annual award given to the “most distinguished” children’s picture book published in the U.S.

Subtle messages of racial equality

There are other reasons to believe that Harold’s skin color was intentional.

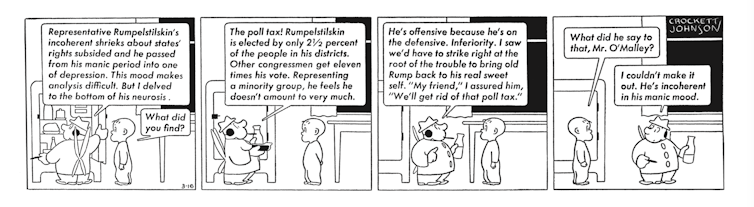

Johnson had advocated for civil rights since the 1940s. In a 1940 cartoon, Johnson satirized the racist propaganda of “Gone with the Wind” – just six weeks before the film won eight Oscars. In 1944, Johnson allowed the National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax to use a three-strip sequence of his comic “Barnaby” that skewers the racist tax. And by 1945, Johnson had joined the End Jim Crow in Baseball Committee.

In 1943, Ursula Nordstrom — Johnson’s editor at Harper — had rejected an anti-racist children’s book written by Johnson’s wife, Ruth Krauss. It was an anthropological look at prejudice that – she hoped – would teach children about the dangers of fascism and antisemitism.

Krauss and Maurice Sendak nonetheless managed to smuggle a message of racial equality into their 1956 book “I Want to Paint My Bathroom Blue”: In one scene, Sendak draws the child’s friends in a rainbow of colors, which was, Krauss later said, “a definite statement in ‘race’ integration.”

Since Sendak and Krauss were working on “I Want to Paint My Bathroom Blue” while Johnson was working on “Harold,” it’s entirely possible that their efforts inspired him to make a comparably subtle political statement by coloring Harold tan.

But contemporary reviewers failed to note the brownness of Harold’s skin. Perhaps excessive subtlety is to blame. Or perhaps the reviewers are not a representative sample of the book’s avid readers. Within a month of its publication, “Harold and the Purple Crayon” sold its initial print run of 10,000 copies, and its publisher ordered a new print run of 7,500 more copies. Surely some of those thousands of readers saw Harold as Black.

A color that offers political cover

Ambiguity can also be politically useful.

Johnson wrote the story while under investigation by the FBI. In the early 1950s, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover thought Johnson was a “concealed Communist,” but by 1954 thought he might be a loyal enough citizen to become an informant. Hoover authorized two FBI agents to approach Johnson. For a couple of months, they sat in a car outside his home in Connecticut, watching him; he refused to come out and talk to them, and they ultimately gave up, four months before the publication of “Harold and the Purple Crayon.”

Since advocates of racial equality in the 1950s risked being censured as “communist,” the subtlety of 10% brown may have granted Johnson and his publisher political cover. Given what Johnson was then facing, making a subtle political statement would have been a wise choice.

It’s also a powerfully inclusive choice. Racial ambiguity makes it easier for readers of any race to identify with Harold. I don’t know whether future musical genius Prince or future U.S. Poet Laureate Rita Dove read Harold as a child of color, but they both said that “Harold and the Purple Crayon” was their favorite childhood book. Harold was the reason Prince adopted purple as his signature color.

Since Harold is racially ambiguous, adults or children of different backgrounds might, in identifying with Harold, see him as a member of their racial or ethnic group.

Harold’s crayon is the embodiment of imaginative possibility. And Harold is whoever you need him to be.![]()

Philip Nel, University Distinguished Professor of English, Kansas State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.