Sa Thi Quy was 43 years old on the morning of March 16, 1968, when Americans came to her hamlet near the coast of the South China Sea in what was then South Vietnam.

“The first time the Americans came, the children followed them. They gave the children sweets to eat. Then they smiled and left. We don’t know their language – they smiled and said OK and so we learned the word OK.”

“The second time they came, we poured them water to drink. They didn’t say anything.”

“The third time they killed everyone.”

The name of her hamlet was My Lai.

Dim memories of a horrific crime

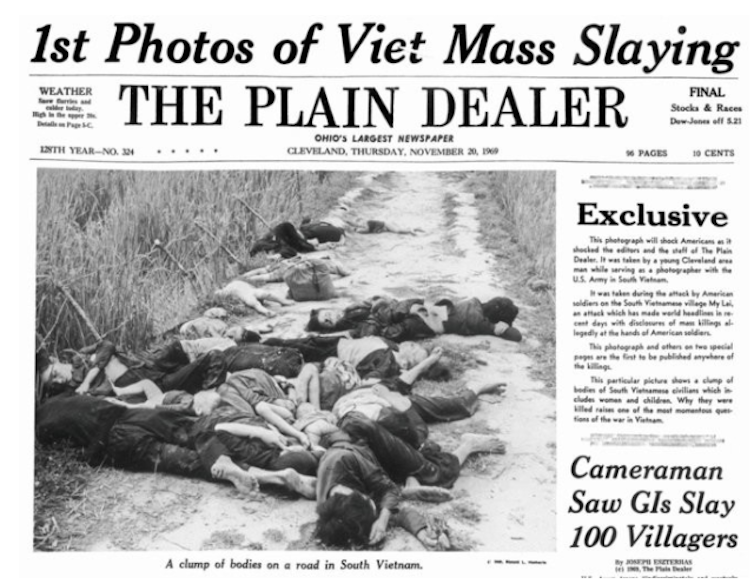

If Americans remember that name at all, they most likely remember that something dark and awful happened there. They are probably fuzzy on the details. Maybe they remember some grainy color photographs of Vietnamese bodies piled in a ditch. Or a lieutenant named Calley.But on this 50th anniversary of what happened in that Vietnamese hamlet, it is worth recalling the grotesque details, in the hope that doing so will help prevent a future My Lai.

It is still an unsettled question about what, exactly, the troops of the Americal Division were ordered to do and who, exactly, issued the orders. What is settled is that for four hours that morning, American young men went on a rampage of killing and rape.

When they finally broke for lunch, the Americans had butchered 504 Vietnamese old men, women, children and babies. No military-aged men were killed. Only one weapon belonging to the Vietnamese was found.

Sometimes, the soldiers shot Vietnamese one at a time. Sometimes they herded them into ditches and machine-gunned them down in groups.

Sometimes it seemed as if the Americans were making a sport out of it.

One soldier threw a wounded elderly man down a well then dropped a grenade in after him. A soldier bayoneted an old man to death.

Another soldier was armed with an M-79 grenade launcher. Other soldiers testified at Army hearings that the man was frustrated that he hadn’t been able to use his weapon, so he herded some women and children together, backed off and fired several explosive rounds into them. Other soldiers with pistols killed those who were only wounded.

In a better-disciplined outfit, the officers in the field would have stopped such violence.

But in this outfit, officers took part in the killing.

‘Blew her brains out’

According to testimony from his men, one company commander, Capt. Ernest Medina, shot and killed a wounded and helpless woman. Lt. William Calley grabbed one woman by the hair and blew her brains out with his .45-caliber pistol. Then he shot to death an infant she’d been carrying. In total, Calley is thought to have killed or ordered killed more than 100 civilians.

It is worth noting that the massacre may never have come to light if it weren’t for a soldier who was an aspiring journalist. Ronald Ridenhour served in the Americal Division in Vietnam at the time of the massacre but was not present at My Lai. Ridenhour got wind of it, interviewed men who had been there and wrote his findings in a letter to 30 members of Congress and the Pentagon.

As the story started to break – mostly due to the efforts of young investigative reporter Seymour Hersh – another soldier who had been in My Lai published the color photos that are the best documentation of the horror at My Lai.

I covered Vietnam for two years as a photojournalist and was in Vietnam when the My Lai story broke. I remember that I was stunned. I’d seen villages burned and Vietnamese pushed around, but nothing even approaching My Lai.

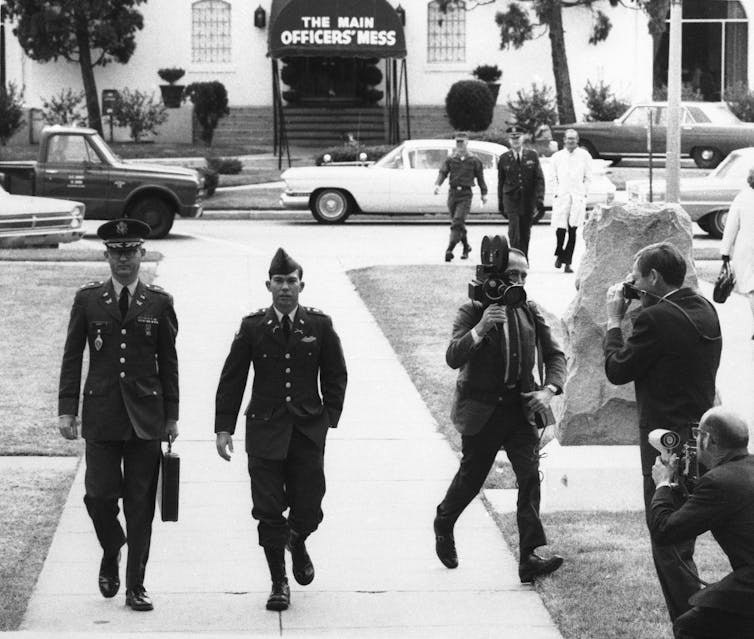

In the wake of all that bad publicity, the Army appointed a highly decorated and well regarded three-star general, Lt. Gen. William R. Peers, to investigate the cover-up. Over four months, he and his staff took sworn testimony from about 400 witnesses. The transcript runs to 20,000 pages.

Ten years ago a sharp producer in London, Celina Dunlop, found out that the testimony had been tape-recorded. I worked on a two-part BBC radio documentary about My Lai, using those tapes. It was the first time I’d heard the voices of the men who took part, describing what they had done and seen.

Their voices haunt me. I used voices to write a play about the massacre – called simply enough, “My Lai” – and in doing so, read all 20,000 pages of their testimony. No writer could do better than their simple, direct description of the horror they let loose on that village.

Heroes amid the carnage

There were really only three Americans who behaved heroically that day. Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson was flying a small scout helicopter with two crewmen, Glenn Andreotti and Lawrence Colburn. They witnessed the massacre from above. When they saw American troops advancing toward a group of old men, women and children, Thompson landed his helicopter between the soldiers and the civilians and ordered his crewmen to shoot the Americans if they opened fire on the civilians. He called other choppers to evacuate the civilians. For that, Thompson was shunned by fellow officers for years afterward.What isn’t usually written about at My Lai are the rapes.

While the exact number may never be known, the Americans raped at least several dozen women and girls, some as young as 12. And then murdered and mutilated many of them.

One soldier, Dennis Bunning of Raymond, California, testified that a sergeant “took one girl there, and drug her into a compartment, like in a hootch there, you know, and hootches don’t have doors or nothing, and you could see, and he raped one girl inside there. And then there was three other guys and one girl all at one time. … A guy would just grab one of the girls there and in one or two incidents they shot the girls when they got done.”

Pham Thi Tuan, who lived in My Lai, told a documentary filmmaker, “Over there a naked woman who had been raped and a virgin girl with her vagina slit open. We don’t know why they behaved liked that.”

‘Failure of leadership’

And that, finally, is the question that is most vexing.How could American boys behave like that? How could they behave like Nazi and Japanese soldiers in World War II?

One excuse frequently offered is that the unit had been hard hit and was in some sort of shock. In fact, the unit had only been in Vietnam for three months and had never been in a firefight. Before My Lai, only five men from the unit had been killed, all by mines or snipers, at a time when Americans were losing 15-20 men per day.

Another excuse is that the men were subpar, draftees, the bottom of a rapidly emptying barrel. But that’s not true either, according to an Army investigation. By every measure – intelligence, education, physical fitness – they were typical of the hundreds of thousands of soldiers who never engaged in such behavior.

In the end, Peers, who headed the investigation, concluded that the massacre was a failure of leadership, from the commanding general on down. He concluded that 28 officers and enlisted men had committed war crimes – murder and rape – or conspired to cover up the crimes.

But in the end, only 14 officers were charged. And only Calley was convicted. President Richard Nixon, bowing to public pressure from those who believed Calley was a scapegoat, commuted his life sentence. He spent three and half years confined, most of that time under house arrest.

Nixon wouldn’t even allow Peers to call it a massacre. The massacre became, instead, “a tragedy of major proportions.”

The darkest side of American exceptionalism is the belief that somehow we are more moral than others and that our troops would never slaughter innocents civilians. Americans need to understand that in every war in the history of humankind, soldiers commit hideous acts. Even our troops. It is inevitable.

Americans need to be prepared to share the moral responsibility for those crimes when we send our young men and women off to fight wars on our behalf.

Robert Hodierne, Chair and Professor of Journalism, University of Richmond

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

No comments:

Post a Comment