Nearly 70 years ago, in December 1948, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. At this time, the UN’s cultural arm, UNESCO, sought to harness the “universal language” of photography to communicate the new system of human rights globally, across barriers of race and language.

UNESCO curated the ground-breaking “Human Rights Exhibition” in 1949, seeking to create a sense of a universal humanity through photographs. It sent portable photo albums around the world, so that the exhibition could be recreated by anyone, anywhere.

In the decades since, visual images have played an important role in defining, contesting, and arguing on behalf of human rights. Photographs are a crucial way of disseminating ideas, and creating a sense of a shared humanity – but they can also justify arguments for conquest and oppression. Here are ten photos that show how we have seen human rights.

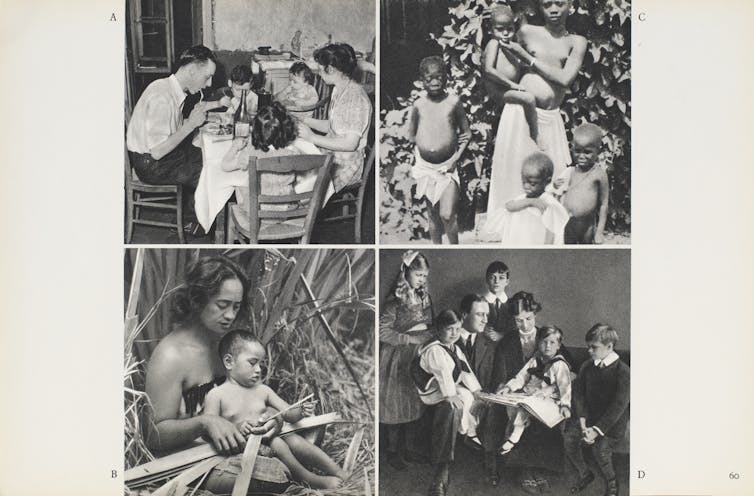

A human ‘family’

Many of UNESCO’s 1949 photographs could be accused of picturing a falsely harmonious human “family” – literally, in this instance, by showing a collage of four families from different cultures, all seemingly alike.

Scenes of war

However a counter-narrative of atrocity and what it termed “struggle” was introduced through scenes of war. There were images of soldiers washed ashore on a beach and a heap of corpses at Buchenwald in a discourse centred upon the violation of human rights. Some visual theorists argue that such images are crucial in proving the existence of distant suffering and injustice. Others have criticised them for exploiting the victims further, or anaesthetising suffering.

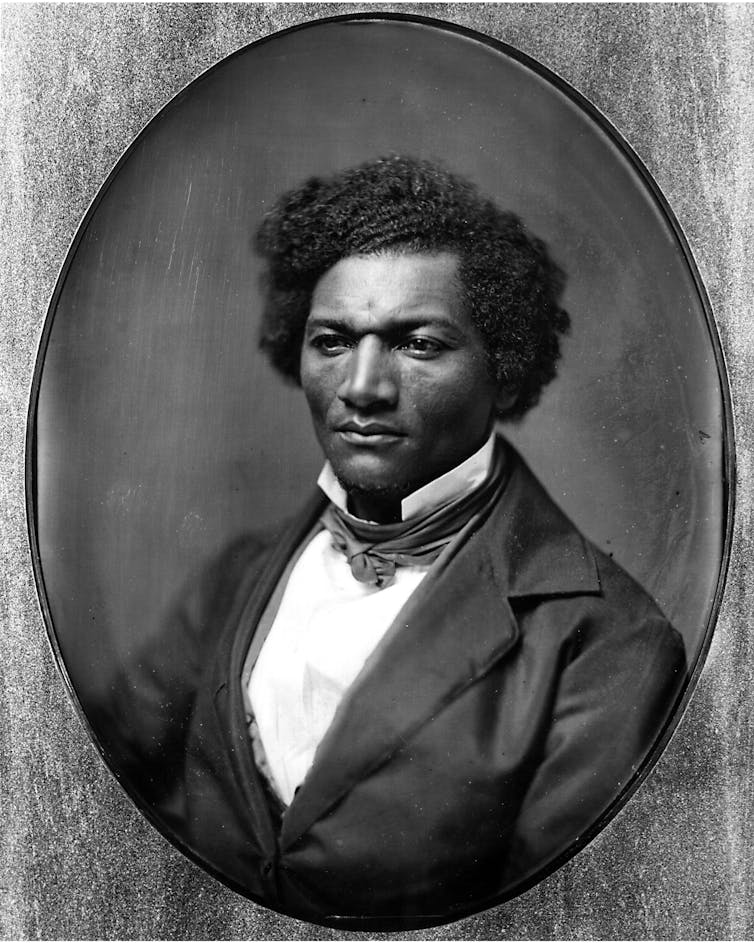

Dignity and humanity

Often, the power of seeing someone very different from ourselves can create a sense of proximity, and the recognition of another’s full humanity. For example, after Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in Maryland in 1838, he became a leading campaigner in the abolitionist movement in the United States. He believed in the power of his dignified and serious photographic portrait to counter racist caricatures, and became the most-photographed man of the 19th century.

A changed context

Sometimes, photographs taken for one purpose can come to have a very different meaning, as the social context for viewing them is transformed. In 1904, during the final throes of the Aceh War, the military doctor H.M. Neeb took a series of now infamous images that showed the massacre of villagers by Dutch KNIL forces in Koetö Réh, where more than 500 people died, 130 of them children. Dutch rulers subsequently used these photographs to argue for the paternalistic colonial state as protector. We now see them as shocking evidence of imperial atrocity.

Biscuits in a revolution

Fifty years later, during the revolution in Indonesia in 1945-50, it became taboo to show the massacre of civilians. Instead, showing soldiers as humanitarians – for instance, distributing biscuits to local children – was the preferred image.

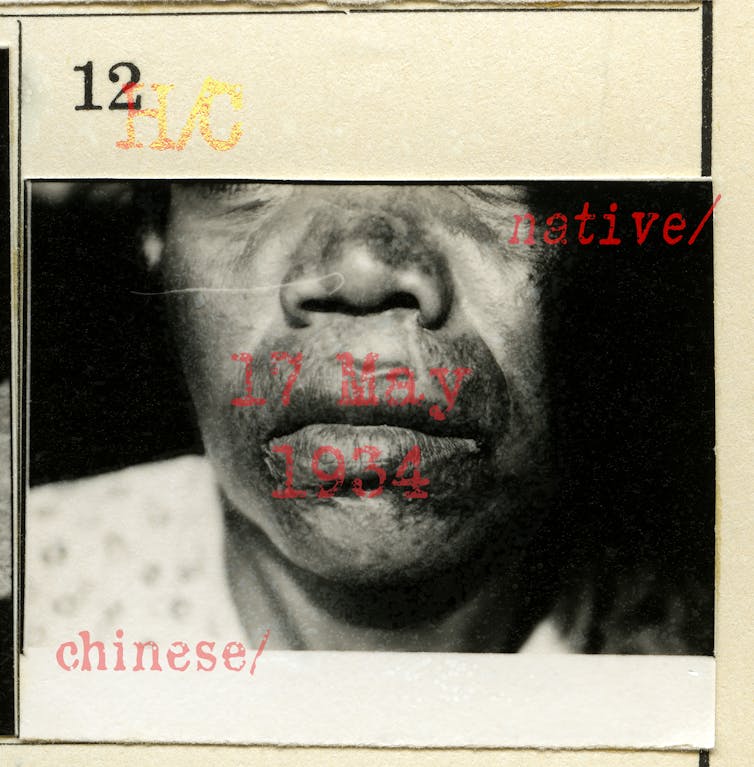

Transforming colonial classification

In Australia, many photographs of Aboriginal people were taken for official purposes, to classify them on racial grounds, or document the “progress” children were making in state homes. However, Aboriginal families now use these photos very differently. Photo-artist Brenda L. Croft uses photography to tell the story of her father Joseph, removed in the 1920s as a child from his Gurindji/Malgnin/Mudburra people of the Victoria River region in the Northern Territory. When he was physically reunited with his mother Bessie in 1974 their reunion was tragically short-lived. She died just seven months later.

Croft uses photography to explore her journey home, re-asserting her connection with places and kin fragmented by the ongoing impact of colonialism. Her “shut/mouth/scream” shows Bessie’s face, cropped from an official mug-shot that classified her on racial grounds. Croft has transformed it into a confronting and emotional portrait.

Documenting protest

Other troubled histories are kept alive in the present through photographs that document protest. Vera Mackie’s images act as a witness to demonstrations staged at the Japanese Embassy in Seoul against the militarised sexual abuse perpetrated by the Japanese in the Asia Pacific War. They focus upon an “icon of peace”: a commemorative statue on the site of the protests.

Evading sterotypes

Australia is a party to international legal treaties such as the UN Refugee Convention, so is obliged to ensure that asylum seekers found to be refugees are not sent back to a country where their life or freedom would be threatened. Yet many find it hard to engage with the plight of refugees currently incarcerated in sites of offshore detention such as Manus Island and Nauru. The Australian government has increasingly restricted media and public access to such places so we have difficulty seeing and understanding what is happening there.Read more: Friday essay: worth a thousand words – how photos shape attitudes to refugees

Australian photojournalists such as Fairfax’s Kate Geraghty have sought to document the refugee experience in ways that evade stereotypes either of victimhood or threat. Geraghty’s photograph of Iranian asylum-seeker Pezhma Gorbani holding his ID card against a bus window after his arrival on Manus Island in 2013 shows his despair and defiance, but also highlights the issue of press access.

‘I was a refugee’

Some refugees have taken matters into their own hands, using social media as an act of protest and political solidarity with others around the globe. Using the hashtag #iwasarefugee, Alisha Fernando showed herself as a baby, asleep aboard a ship after her Vietnamese family was rescued at sea.

Asserting control

Fernando contrasted this with a photo of herself and the captain of the boat that had rescued her, taken 21 years later, after she had become an Australian citizen. In this way refugees are asserting some control over their own image and eloquently demonstrating their humanity.

While visual theorists are often wary of the power of images to manipulate viewers or exploit their subjects, we must not assume that images are fixed in their meaning and effects. We cannot do without images that reveal atrocity, evoke fellow-feeling, and construct a shared humanity.

The book Visualising Human Rights has just been published by UWA Publishing and includes contributions from Sharon Sliwinski, Susie Protschky, Brenda L.Croft, Vera Mackie, Mary Tomsic, Fay Anderson, Suvendrini Perera and Joseph Pugliese.

Jane Lydon, Wesfarmers Chair of Australian History, University of Western Australia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment