A widely circulated still from the set of Martin Scorsese’s latest film, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” shows the director sitting in a church pew. Next to him is Lily Gladstone, who plays the role of Mollie Kyle, an Osage woman whose family is targeted as part of a broader conspiracy by white Americans to steal the tribe’s wealth, to the point of marrying and killing its members.

In the photograph, Scorsese appears to hold rosary beads, a common devotional object for many Catholics. Mollie is Catholic, so the rosary makes sense as a prop. But as a scholar of religion and film, I’m struck by how it calls to mind the director’s own complex Catholicism and its imprint on his decades of filmmaking.

Scorsese stands in a long line of Catholic American filmmakers, stretching back to the 1930s and 1940s – one that includes Irish Americans John Ford and Leo McCarey, and Italian immigrant Frank Capra. At a time when Catholicism still seemed foreign to many Americans, those directors helped normalize the faith, making it seem like part of a shared American story.

Yet in his films, Scorsese has taken a much more personal approach to exploring Catholic faith and experience. He doesn’t feel the need to defend the religion or burnish its image. His movies are steeped in Catholic sensibilities, but embrace painful questions that often accompany belief: what it means to hold on to religious commitment in a world where God can seem absent.

From altar boy to auteur

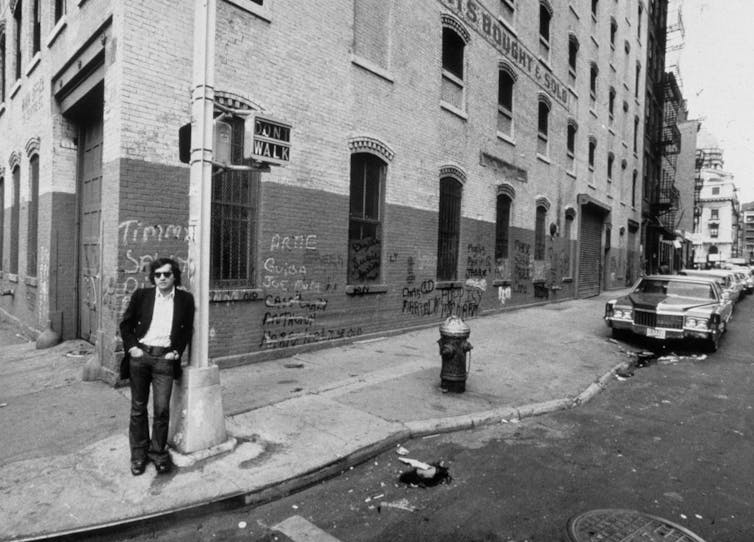

Scorsese has often spoken of his Catholic background. Born in New York City’s Little Italy, he went to Catholic schools and served as an altar boy at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, which appeared in his early masterpiece “Mean Streets.” Scorsese even began seminary training, but he quickly realized the priesthood was not for him.

Yet the church proved influential. Scorsese has described St. Patrick’s as a spiritual alternative to the violence in the streets around his neighborhood. A priest introduced the young Scorsese to classical music and books that widened his cultural horizons.

A similar tension runs through many of his films: Catholic devotion, mystery and ritual interwoven with ruthless crime. Indeed, the struggle with faith amid brutality is a theme Scorsese returns to over and over, asking what religion might have to offer the world as it actually exists, with all its cruelties, greed and despair.

Presence and absence

That struggle can be described as one between “presence” and “absence,” to use the terms of religious studies scholar Robert A. Orsi.

Religious presence refers to all the ways people experience their gods’ existence in the world and in their lives. For Catholics, for example, the Eucharist is not just a symbol of Christ; the consecrated bread and wine in Communion actually become Jesus’ flesh and blood, according to Catholic teaching.

Orsi describes religious absence, on the other hand, as the experience of doubt and spiritual struggle about a god not felt directly on Earth.

Both presence and absence shape Scorsese’s rendering of religion. God’s absence takes the form of violence and greed in his films. But some characters also carry their gods with them in the world. This is most dramatically seen in “Silence,” released in 2016, which was based on the novel by Japanese Catholic writer Shusaku Endo.

“Silence” is the story of two Jesuit missionaries who travel to 17th century Japan in search of their mentor, another Jesuit who is believed to have renounced the faith during a wave of violent persecutions. One of them, Father Rodrigues, profoundly questions his own faith after witnessing the torture of Japanese Christians.

Why, he wonders, does God allow such suffering? Eventually he himself will renounce his faith in order to save the lives of those to whom he ministers.

The silence of God is the film’s major preoccupation, yet it is filled with devotional imagery. At the climax of the film, Rodrigues tramples on an image of Christ in order to end the torture of other Christians. But just at that moment, he experiences the presence of his God.

The very final scene depicts his burial, years after the film’s main events – a small crucifix clasped in his hand.

Penance ‘in the streets’

This preoccupation with Catholicism stretches back to Scorsese’s 1973 breakthrough film, “Mean Streets.” Harvey Keitel plays a young Italian American man, Charlie, who grapples with his faith in the unforgiving world of New York’s Lower East Side.

Presence, as Orsi points out, is often as much a burden as a solace. Indeed, part of the emotional power in “Mean Streets” lies in Charlie’s own impatience toward Catholic practices and rules. He wants the freedom to be Catholic in his own way.

“You don’t make up for your sins in the church,” he insists in the opening voice-over. “You do it in the streets. You do it at home. The rest is bullshit, and you know it.”

Over the years, Scorsese’s own ambitions have led him far beyond the streets of Little Italy. A number of his films have little to do with religion. Yet movies such as “Casino,” “The Aviator” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” elaborate the same basic question as “Mean Streets”: What is important in a world that so often feels dominated by absence, money and violence? Through a long career, Scorsese has framed both the sacred and profane as compelling but competing forces of human desire.

Shortly before the release of “Silence,” Scorsese visited St. Patrick’s during an interview with The New York Times. “I never left,” he said. “In my mind, I am here every day.”

One might take him at his word. Even in his most recent movie, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” a Catholic sensibility sneaks through in numerous ways. Characters attend Mass at parish churches and bury their dead on consecrated Catholic ground.

Further, the film’s attention to Osage religious practices demonstrates Scorsese’s sensitivity to the power of ritual and devotion. The movie opens with the burial of a ceremonial pipe, highlighting how objects can assume sacred significance. As Mollie’s mother dies, she has a vision of the elders.

But the questions that haunt Scorsese hang over moments that hardly feel religious, too.

Toward the end of the film, when Mollie asks her duplicitous husband, Ernest, to come clean, his refusal to fully confess the harm he did to her and her family epitomizes the depths of his ethical emptiness. Her silence as she gets up and leaves, with an FBI agent standing quietly in the corner, offers a more powerful moral indictment than any legal sentence. The refusal to pay for one’s sins at home and in the streets has rarely looked so damning.![]()

Anthony Smith, Associate Professor of Religious Studies, University of Dayton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment