The new tax reform bill has led to an intense debate over whether it would help or hurt the poor. Tax reform in general raises critical issues about whether the government should redistribute income and promote equality in the first place.

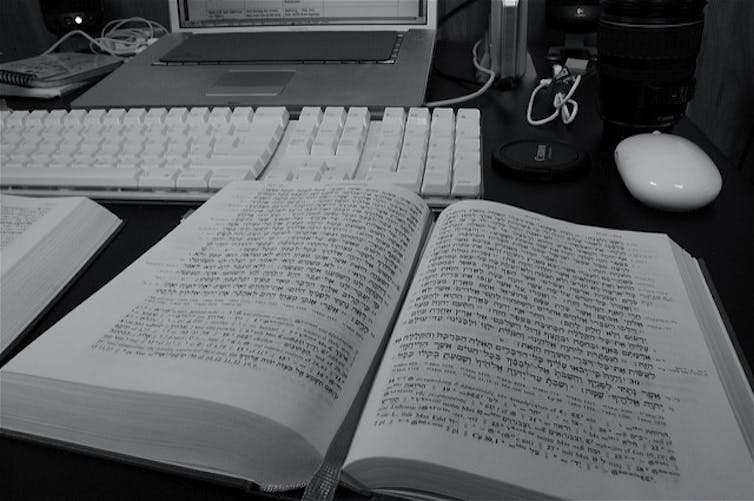

Jews and Christians look to the Bible for guidance about these questions. And while the Bible is clear about aiding the poor, it does not provide easy answers about taxing the rich. But even so, over the centuries biblical principles have provided an understanding on how to help the needy.

The Hebrew Bible and the poor

The Hebrew Bible has extensive regulations that require the wealthy to set aside for the poor a portion of the crops that they grow.The Bible’s Book of Leviticus states that the needy have a right to the “leftovers” of the harvest. Farmers are also prohibited from reaping the corners of their fields so that the poor can access and use for their own food the crops grown there.

In Deuteronomy, the fifth book of the Bible, there is the requirement that every three years, 10 percent of a person’s produce should be given to “foreigners, the fatherless and widows.”

Helping the poor is a way of “paying rent” to God, who is understood to actually own all property and who provides the rain and sun needed to grow crops. In fact, every seventh year, during the sabbatical year, all debts are forgiven and everything that grows in the land is made available freely to all people. Then, in the great jubilee, celebrated every 50 years, property returns to its original owner. This means that, in the biblical model, no one can permanently hold onto something that finally belongs to God.

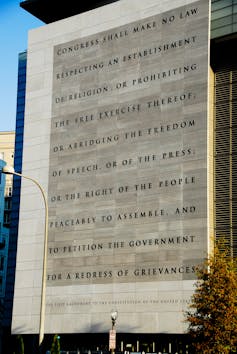

Christians and taxes

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus says, “whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.” Jesus thus joins respect for the poor with respect for God. In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus also states “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s,” which is often interpreted as requiring Christians to pay taxes.Throughout Christian history, taxation has been considered an essential government responsibility.

The Protestant reformers Martin Luther and John Calvin drew upon Psalm 72 to argue that a “righteous” government helps the poor.

In 16th-century England, “poor laws” were passed to aid “the deserving poor and unemployed.” The “deserving poor” were children, the old and the sick. By contrast, the “undeserving poor” were beggars and criminals and they were usually put in prison. These laws also shaped early American approaches to social welfare.

The common good

Over the last two centuries, new economic realities have raised new challenges in applying biblical principles to economic life. Approaches not foreseen in biblical times emerged in an attempt to respond to new situations.

In the 19th century, organizations like the Salvation Army believed that Christians should go out of the churches and into the streets to care for the destitute. During this period, the United States also saw the rise of the social gospel movement that emphasized biblical ideals of justice and equality. Poverty was considered a social problem that required a comprehensive social – and governmental – response.

The idea that government has an important role to play in human flourishing was made by Pope Leo XIII in his 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum. In it, the pope argued that governments should promote “the common good.” Catholicism defines the “common good” as the “conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfillment more fully and more easily.”

While human fulfillment is not just about material comfort, the Catholic Church has always maintained that citizens should have access to food, housing and health care. As the Catholic Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church makes clear, taxation is necessary because government should “harmonize” society in a just way.

And when it comes to taxes, no one should pay more or less than they are able. As Pope John XXIII wrote in 1961, taxation must “be proportioned to the capacity of the people contributing.”

In other words, believing that helping the poor is simply an individual or private responsibility ignores the scope and complexity of the world we live in.

Mercy, not the market

Human life has become more interconnected. In today’s globalized economy, decisions made in the heartland of China impact the American Midwest. But even with this deepening interdependence, by some measures, inequality has risen worldwide. In the United States alone, the top 1 percent possess an increasingly larger share of national income.

When it comes to helping the poor in these current times, some argue that cutting taxes on individuals and corporations will stimulate economic growth and create jobs – called the “trickle-down effect,” in which money flows from those at the top of the social pyramid down to lower levels.

Pope Francis, however, argues that “trickle-down” economics places a “crude and naive trust in those wielding economic power.” In the pope’s view, an ethics of mercy, not the market, should shape society.

But given the Jewish and Christian commitment to the poor, the question is perhaps a factual one: What social policy does the most good?

In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus taught:

“Give, and you will receive. Your gift will return to you in full.”

Mathew Schmalz, Associate Professor of Religion, College of the Holy Cross

This article was originally published on The Conversation.