Note from Editor of The Conversation US: This is a revised version of the original piece. We have done so to make explicit the author’s expertise with regard to the subject of this article. We have also incorporated important context that was missing in the original version.

The question of whether a god exists is heating up in the 21st century. According to a Pew survey, the percent of Americans having no religious affiliation reached 23 percent in 2014. Among such “nones,” 33 percent said that they do not believe in God – an 11 percent increase since only 2007.

Such trends have ironically been taking place even as, I would argue, the probability for the existence of a supernatural god have been rising. In my 2015 book, “God? Very Probably: Five Rational Ways to Think about the Question of a God,” I look at physics, the philosophy of human consciousness, evolutionary biology, mathematics, the history of religion and theology to explore whether such a god exists. I should say that I am trained originally as an economist, but have been working at the intersection of economics, environmentalism and theology since the 1990s.

Laws of math

In 1960 the Princeton physicist – and subsequent Nobel Prize winner – Eugene Wigner raised a fundamental question: Why did the natural world always – so far as we know – obey laws of mathematics?

As argued by scholars such as Philip Davis and Reuben Hersh, mathematics exists independent of physical reality. It is the job of mathematicians to discover the realities of this separate world of mathematical laws and concepts. Physicists then put the mathematics to use according to the rules of prediction and confirmed observation of the scientific method.

But modern mathematics generally is formulated before any natural observations are made, and many mathematical laws today have no known existing physical analogues.

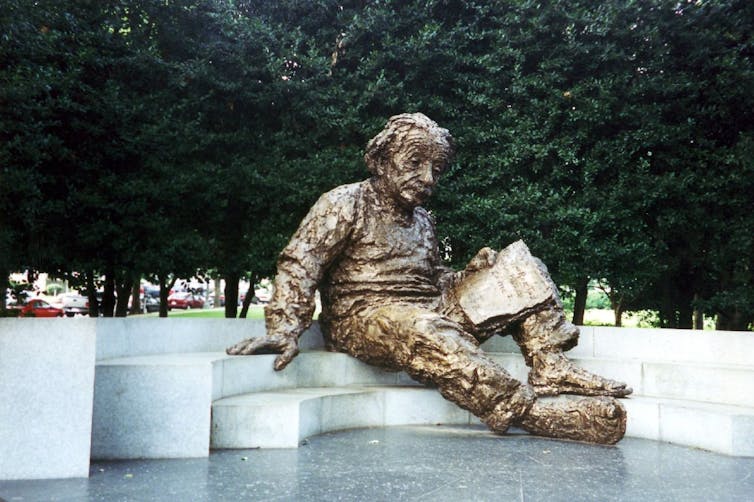

Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity, for example, was based on theoretical mathematics developed 50 years earlier by the great German mathematician Bernhard Riemann that did not have any known practical applications at the time of its intellectual creation.

In some cases the physicist also discovers the mathematics. Isaac Newton was considered among the greatest mathematicians as well as physicists of the 17th century. Other physicists sought his help in finding a mathematics that would predict the workings of the solar system. He found it in the mathematical law of gravity, based in part on his discovery of calculus.

At the time, however, many people initially resisted Newton’s conclusions because they seemed to be “occult.” How could two distant objects in the solar system be drawn toward one another, acting according to a precise mathematical law? Indeed, Newton made strenuous efforts over his lifetime to find a natural explanation, but in the end he could say only that it is the will of God.

Despite the many other enormous advances of modern physics, little has changed in this regard. As Wigner wrote, “the enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious and there is no rational explanation for it.”

In other words, as I argue in my book, it takes the existence of some kind of a god to make the mathematical underpinnings of the universe comprehensible.

Math and other worlds

In 2004 the great British physicist Roger Penrose put forward a vision of a universe composed of three independently existing worlds – mathematics, the material world and human consciousness. As Penrose acknowledged, it was a complete puzzle to him how the three interacted with one another outside the ability of any scientific or other conventionally rational model.

How can physical atoms and molecules, for example, create something that exists in a separate domain that has no physical existence: human consciousness?

It is a mystery that lies beyond science.

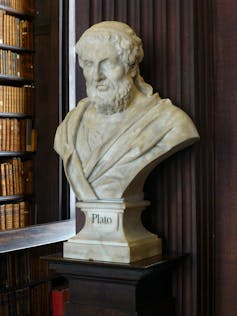

This mystery is the same one that existed in the Greek worldview of Plato, who believed that abstract ideas (above all mathematical) first existed outside any physical reality. The material world that we experience as part of our human existence is an imperfect reflection of these prior formal ideals. As the scholar of ancient Greek philosophy, Ian Mueller, writes in “Mathematics And The Divine,” the realm of such ideals is that of God.

Indeed, in 2014 the MIT physicist Max Tegmark argues in “Our Mathematical Universe” that mathematics is the fundamental world reality that drives the universe. As I would say, mathematics is operating in a god-like fashion.

The mystery of human consciousness

The workings of human consciousness are similarly miraculous. Like the laws of mathematics, consciousness has no physical presence in the world; the images and thoughts in our consciousness have no measurable dimensions.

Yet, our nonphysical thoughts somehow mysteriously guide the actions of our physical human bodies. This is no more scientifically explicable than the mysterious ability of nonphysical mathematical constructions to determine the workings of a separate physical world.

Until recently, the scientifically unfathomable quality of human consciousness inhibited the very scholarly discussion of the subject. Since the 1970s, however, it has become a leading area of inquiry among philosophers.

Recognizing that he could not reconcile his own scientific materialism with the existence of a nonphysical world of human consciousness, a leading atheist, Daniel Dennett, in 1991 took the radical step of denying that consciousness even exists.

Finding this altogether implausible, as most people do, another leading philosopher, Thomas Nagel, wrote in 2012 that, given the scientifically inexplicable – the “intractable” – character of human consciousness, “we will have to leave [scientific] materialism behind” as a complete basis for understanding the world of human existence.

As an atheist, Nagel does not offer religious belief as an alternative, but I would argue that the supernatural character of the workings of human consciousness adds grounds for raising the probability of the existence of a supernatural god.

Evolution and faith

Evolution is a contentious subject in American public life. According to Pew, 98 percent of scientists connected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science “believe humans evolved over time” while only a minority of Americans “fully accept evolution through natural selection.”

As I say in my book, I should emphasize that I am not questioning the reality of natural biological evolution. What is interesting to me, however, are the fierce arguments that have taken place between professional evolutionary biologists. A number of developments in evolutionary theory have challenged traditional Darwinist – and later neo-Darwinist – views that emphasize random genetic mutations and gradual evolutionary selection by the process of survival of the fittest.

From the 1970s onwards, the Harvard evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould created controversy by positing a different view, “punctuated equilibrium,” to the slow and gradual evolution of species as theorized by Darwin.

In 2011, the University of Chicago evolutionary biologist James Shapiro argued that, remarkably enough, many micro-evolutionary processes worked as though guided by a purposeful “sentience” of the evolving plant and animal organisms themselves. “The capacity of living organisms to alter their own heredity is undeniable,” he wrote. “Our current ideas about evolution have to incorporate this basic fact of life.”

A number of scientists, such as Francis Collins, director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health, “see no conflict between believing in God and accepting the contemporary theory of evolution,” as the American Association for the Advancement of Science points out.

For my part, the most recent developments in evolutionary biology have increased the probability of a god.

Miraculous ideas at the same time?

For the past 10,000 years at a minimum, the most important changes in human existence have been driven by cultural developments occurring in the realm of human ideas.

In the Axial Age (commonly dated from 800 to 200 B.C.), world-transforming ideas such as Buddhism, Confucianism, the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle, and the Hebrew Old Testament almost miraculously appeared at about the same time in India, China, ancient Greece and among the Jews in the Middle East, groups having little interaction with one another.

The development of the scientific method in the 17th century in Europe and its modern further advances have had at least as great a set of world-transforming consequences. There have been many historical theories, but none capable, I would argue, of explaining as fundamentally transformational a set of events as the rise of the modern world. It was a revolution in human thought, operating outside any explanations grounded in scientific materialism, that drove the process.

That all these astonishing things happened within the conscious workings of human minds, functioning outside physical reality, offers further rational evidence, in my view, for the conclusion that human beings may well be made “in the image of [a] God.”

Different forms of worship

In his commencement address to Kenyon College in 2005, the American novelist and essayist David Foster Wallace said that: “Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship.”

Even though Karl Marx, for example, condemned the illusion of religion, his followers, ironically, worshiped Marxism. The American philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre thus wrote that for much of the 20th century, Marxism was the “historical successor of Christianity,” claiming to show the faithful the one correct path to a new heaven on Earth.

In several of my books, I have explored how Marxism and other such “economic religions” were characteristic of much of the modern age. So Christianity, I would argue, did not disappear as much as it reappeared in many such disguised forms of “secular religion.”

That the Christian essence, as arose out of Judaism, showed such great staying power amidst the extraordinary political, economic, intellectual and other radical changes of the modern age is another reason I offer for thinking that the existence of a god is very probable.![]()

Robert H. Nelson, Professor of Public Policy, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.