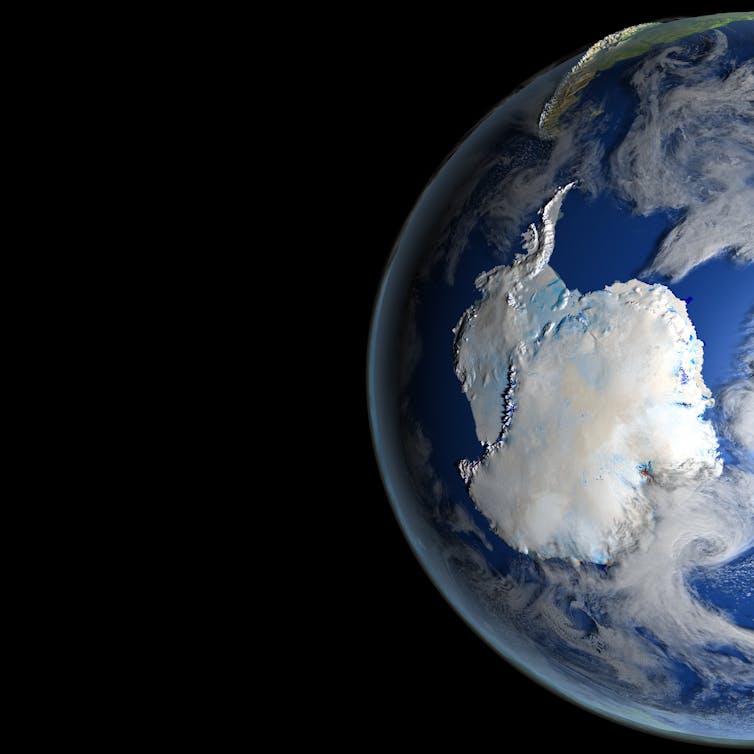

Scientists have known for a long time that as climate change started to heat up the Earth, its effects would be most pronounced in the Arctic. This has many reasons, but climate feedbacks are key. As the Arctic warms, snow and ice melt, and the surface absorbs more of the sun’s energy instead of reflecting it back into space. This makes it even warmer, which causes more melting, and so on.

This expectation has become a reality that I describe in my new book “Brave New Arctic.” It’s a visually compelling story: The effects of warming are evident in shrinking ice caps and glaciers and in Alaskan roads buckling as permafrost beneath them thaws.

But for many people the Arctic seems like a faraway place, and stories of what is happening there seem irrelevant to their lives. It can also be hard to accept that the globe is warming up while you are shoveling out from the latest snowstorm.

Since I have spent more than 35 years studying snow, ice and cold places, people often are surprised when I tell them I once was skeptical that human activities were playing a role in climate change. My book traces my own career as a climate scientist and the evolving views of many scientists I have worked with. When I first started working in the Arctic, scientists understood it as a region defined by its snow and ice, with a varying but generally constant climate. In the 1990s, we realized that it was changing, but it took us years to figure out why. Now scientists are trying to understand what the Arctic’s ongoing transformation means for the rest of the planet, and whether the Arctic of old will ever be seen again.

Evidence piles up

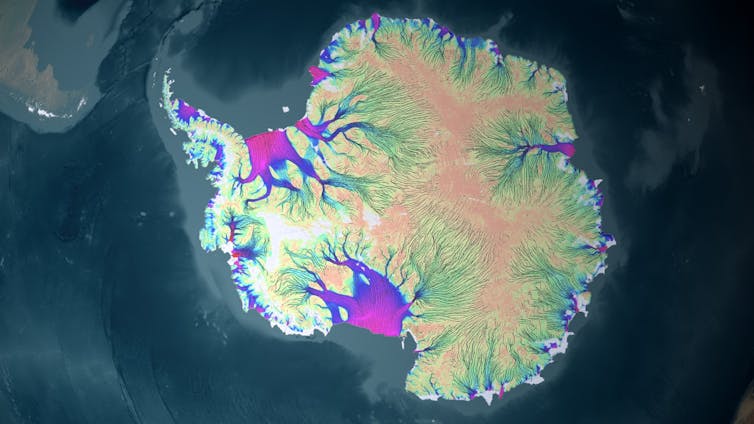

Evidence that the Arctic is warming rapidly extends far beyond shrinking ice caps and buckling roads. It also includes a melting Greenland ice sheet; a rapid decline in the extent of the Arctic’s floating sea ice cover in summer; warming and thawing of permafrost; shrubs taking over areas of tundra that formerly were dominated by sedges, grasses, mosses and lichens; and a rise in temperature twice as large as that for the globe as a whole. This outsized warming even has a name: Arctic amplification.The Arctic began to stir in the early 1990s. The first signs of change were a slight warming of the ocean and an apparent decline in sea ice. By the end of the decade, it was abundantly clear that something was afoot. But to me, it looked like natural climate variability. As I saw it, shifts in wind patterns could explain a lot of the warming, as well as loss of sea ice. There didn’t seem to be much need to invoke the specter of rising greenhouse gas levels.

In 2000 I teamed up with a number of leading researchers in different fields of Arctic science to undertake a comprehensive analysis of all evidence of change that we had seen and how to interpret it. We concluded that while some changes, such as loss of sea ice, were consistent with what climate models were predicting, others were not.

To be clear, we were not asking whether the impacts of rising greenhouse gas concentrations would appear first in the Arctic, as we expected. The science supporting this projection was solid. The issue was whether those impacts had yet emerged. Eventually they did – and in a big way. Sometime around 2003, I accepted the overwhelming evidence of human-induced warming, and started warning the public about what the Arctic was telling us.

Seeing is believing

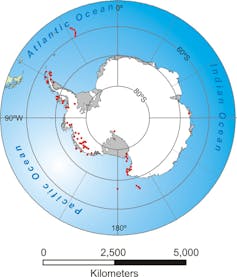

Climate change really hit home for me when when I found out that two little ice caps in the Canadian Arctic I had studied back in 1982 and 1983 as a young graduate student had essentially disappeared.Bruce Raup, a colleague at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, has been using high-resolution satellite data to map all of the world’s glaciers and ice caps. It’s a moving target, because most of them are melting and shrinking – which contributes to sea level rise.

One day in 2016, as I walked past Bruce’s office and saw him hunched over his computer monitor, I asked if we could check out those two ice caps. When I worked on them in the early 1980s, the larger one was perhaps a mile and a half across. Over the course of two summers of field work, I had gotten to know pretty much every square inch of them.

When Bruce found the ice caps and zoomed in, we were aghast to see that they had shrunk to the size of a few football fields. They are even smaller today - just patches of ice that are sure to disappear in just a few years.

Today it seems increasingly likely that what is happening in the Arctic will reverberate around the globe. Arctic warming may already be influencing weather patterns in the middle latitudes. Meltdown of the Greenland ice sheet is having an increasing impact on sea level rise. As permafrost thaws, it may start to release carbon dioxide and methane to the atmosphere, further warming the climate.

Mark Serreze, Research Professor of Geography and director, National Snow and Ice Data Center, University of Colorado

This article was originally published on The Conversation.