“The battle to feed all of humanity is over,” Stanford biologist and ecologist Paul Erhlich declared on the first page of his 1968 best-seller, “The Population Bomb.” Because the “stork had passed the plow,” he predicted, “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death.”

Ehrlich’s book identified dramatically accelerating world population growth as the central underlying cause of myriad problems, from a food crisis in India to the Vietnam War to smog and urban riots in the United States. It sold more than 2 million copies and went through 20 reprints by 1971. Ehrlich appeared more than 20 times on NBC’s “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson”, and became the first president of Zero Population Growth, a Washington D.C.–based advocacy organization, while remaining a professor at Stanford.

“The Population Bomb” created more space to hold radical views on population matters, but its impact was fleeting, and maybe even harmful to the population movement. By the early 1970s, many critics were savaging Ehrlich and the larger goal of achieving zero population growth. And the politics of “morning in America” in the 1980s successfully marginalized Erhlich as a doomsdayer.

However, as a historian who has studied debates about population growth throughout U.S. history, I believe that Ehrlich’s warnings deserve a new and less hysterical hearing. While Ehrlich has acknowledged significant errors, he was correct that lowering birth rates was – and remains – a crucial plank in addressing global environmental crises.

A Malthusian warning

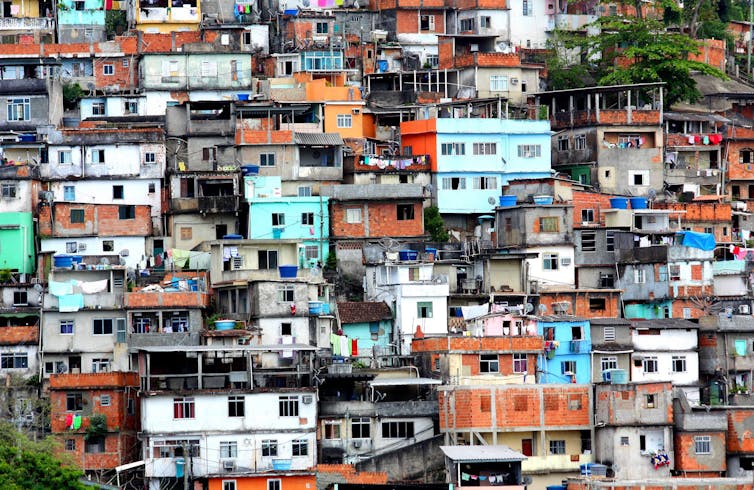

Ehrlich drew on nearly 200 years of thinking inspired by British pastor and political economist Robert Thomas Malthus. In his 1798 study, “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” Malthus famously predicted that “geometric” population growth would overwhelm “arithmetic” gains in agricultural production, leading to wars, famines and societal collapse.Fears of the potentially dangerous social and ecological effects of population growth intensified after World War II. Global population surged as public health improved greatly in developing nations, increasing life expectancy. At the same time, the new science of ecology demonstrated the fragility of Earth’s interconnected systems. And the Cold War promoted worries that population-induced poverty would breed communism.

Mainstream advocates of arresting population growth emphasized better access to family planning and education, but Ehrlich had no use for such baby steps. “Well-spaced children will starve, vaporize in thermonuclear war, or die of plague just as well as unplanned children,” he wrote.

Technological optimists pointed to the “Green Revolution” in agriculture, which had vastly increased crop yields up until the late 1960s. But Erhlich, echoing a growing chorus of farmers and agricultural scientists, warned that pesticides ruined the environment and would eventually backfire as weeds and pests developed resistance.

Erhlich never called population the only variable. With physicist John Holdren, he proposed the I = P x A x T formula, which describes human impact as the product of population, affluence (the effects of consumption) and technology.

Nonetheless, Ehrlich believed that population was the key multiplier and massive reductions in global population were critical for human survival. He hoped that a combination of policy carrots and sticks would reduce fertility sufficiently and preserve voluntary family planning. But he held out the possibility that coercive measures, including compulsory sterilizations, might be needed.

Backlash and a new population politics

Millions of Americans shared Ehrlich’s anxieties in 1968. Concerns about the ecological impact of global population growth had helped birth modern American environmentalism. Feminists cited overpopulation to buttress the case for reproductive and abortion rights. Politicians on both sides of the aisle urged action to lower birth rates, and Republican President Richard Nixon signed into law a Commission on Population Growth and the American Future.But the “culture wars” of the 1970s subsumed and reconfigured population issues. On the right, the “pro-life” movement that crystallized in the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision considered any talk of population reduction anathema.

China’s one-child policy, launched around 1980, led to serious human rights abuses that allowed anti–family planning conservatives to paint all population programs in a negative light. Conservatives subsequently ignored China’s significant reforms to the policy, as well as research indicating that slowing population growth contributed to China’s economic miracle.

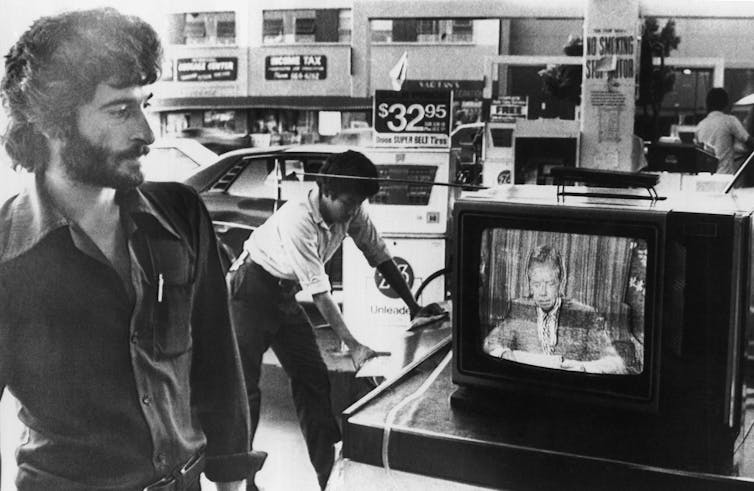

Moreover, newly ascendant anti-Keynesian economists rejected an older consensus that slowing population growth would yield economic benefits. These market-oriented economists asserted that denser populations created economies of scale, and that individual fertility decisions would adjust to any temporary population problems. President Ronald Reagan, who once had dabbled with Malthusianism, tellingly labeled advocates who worried about scarce resources “Doomsday prophets.”

After Congress eliminated national-origin immigration quotas in 1965, immigration rose steadily and accounted for a growing share of population growth in the U.S. In this context, white liberals increasingly risked being branded racist for supporting population reduction.

By the late 1970s, both liberals and conservatives had bought into exaggerated talk of an “aging crisis” – too few workers to pay for the bulge of baby boomers headed toward retirement. This perspective bolstered calls for higher birth rates and further reduced the sting of the overpopulation critique.

An unsolved equation

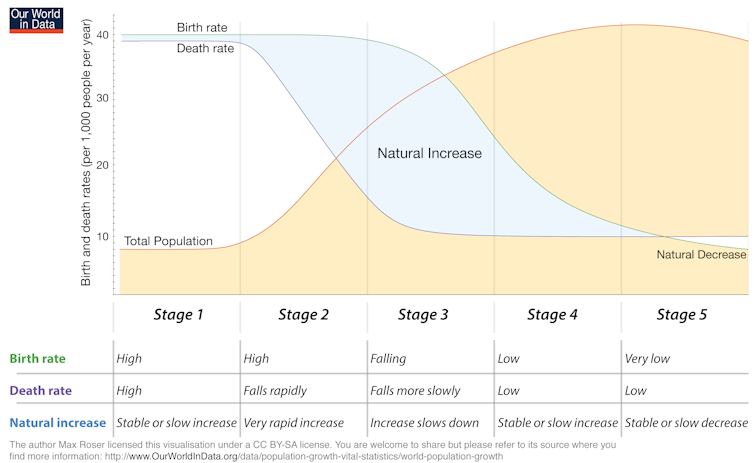

Today Ehrlich is a largely forgotten prophet, although some small population-centric organizations continue to tilt at windmills and the mainstream press occasionally dips its toes in the water. After some very public rifts over immigration policy, mainstream environmental groups generally avoid or downplay the issue. Meanwhile, the Right continues to dismiss talk of population problems.Looking back with the benefit of time, it’s clear Ehrlich was wrong to view population as all-encompassing. In addition, the global total fertility rate has declined more than he anticipated – although the development and modernization that has helped lower birth rates, a process known as the demographic transition, comes at great environmental cost.

Ehrlich underestimated human ingenuity. And for now, one can reasonably argue that food insecurity remains primarily political rather than technological. In Ehrlich’s own words, the book’s weaknesses were “not [focusing] enough on overconsumption and equity issues.”

But he got much right, even if many details and his timing were off. Global population has increased at a remarkably steady rate since 1968, and the United Nations projects that it will reach 9.8 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100. Scientists continue to extend his prescient warnings that efforts to feed all these people through pesticide-intensive monoculture may backfire. And although Ehrlich exaggerated the threat of mass starvation, about 8,500 young children die from malnutrition every day.

Human-driven climate change is an overriding threat, and is unambiguously worsened by population growth. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that limiting warming in this century to 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius) would require cutting global greenhouse gas emissions 40 to 70 percent by 2050 and nearly eliminating them by 2100. “Globally, economic and population growth continue to be the most important drivers of increases in CO2 emissions from fossil fuel combustion,” the panel observes.

Derek Hoff, Associate Professor, Lecturer in Business and Humanities, University of Utah

This article was originally published on The Conversation.