According to the publisher’s editor-at-large, 2023 represented ‘a kind of crisis of authenticity.’

lambada/E+ via Getty Images

Roger J. Kreuz, University of Memphis

According to the publisher’s editor-at-large, 2023 represented ‘a kind of crisis of authenticity.’

lambada/E+ via Getty Images

Roger J. Kreuz, University of Memphis

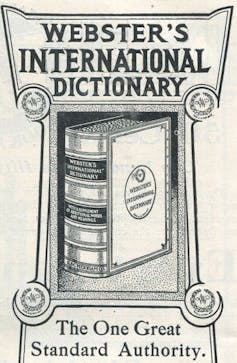

When Merriam-Webster announced that its word of the year for 2023 was “authentic,” it did so with over a month to go in the calendar year.

Even then, the dictionary publisher was late to the game.

In a lexicographic form of Christmas creep, Collins English Dictionary announced its 2023 word of the year, “AI,” on Oct. 31. Cambridge University Press followed suit on Nov. 15 with “hallucinate,” a word used to refer to incorrect or misleading information provided by generative AI programs.

At any rate, terms related to artificial intelligence appear to rule the roost, with “authentic” also falling under that umbrella.

AI and the authenticity crisis

For the past 20 years, Merriam-Webster, the oldest dictionary publisher in the U.S., has chosen a word of the year – a term that encapsulates, in one form or another, the zeitgeist of that past year. In 2020, the word was “pandemic.” The next year’s winner? “Vaccine.”

“Authentic” is, at first glance, a little less obvious.

According to the publisher’s editor-at-large, Peter Sokolowski, 2023 represented “a kind of crisis of authenticity.” He added that the choice was also informed by the number of online users who looked up the word’s meaning throughout the year.

The word “authentic,” in the sense of something that is accurate or authoritative, has its roots in French and Latin. The Oxford English Dictionary has identified its usage in English as early as the late 14th century.

And yet the concept – particularly as it applies to human creations and human behavior – is slippery.

Is a photograph made from film more authentic than one made from a digital camera? Does an authentic scotch have to be made at a small-batch distillery in Scotland? When socializing, are you being authentic – or just plain rude – when you skirt niceties and small talk? Does being your authentic self mean pursuing something that feels natural, even at the expense of cultural or legal constraints?

The more you think about it, the more it seems like an ever-elusive ideal – one further complicated by advances in artificial intelligence.

How much human touch?

Intelligence of the artificial variety – as in nonhuman, inauthentic, computer-generated intelligence – was the technology story of the past year.

At the end of 2022, OpenAI publicly released ChatGPT 3.5, a chatbot derived from so-called large language models. It was widely seen as a breakthrough in artificial intelligence, but its rapid adoption led to questions about the accuracy of its answers.

The chatbot also became popular among students, which compelled teachers to grapple with how to ensure their assignments weren’t being completed by ChatGPT.

Issues of authenticity have arisen in other areas as well. In November 2023, a track described as the “last Beatles song” was released. “Now and Then” is a compilation of music originally written and performed by John Lennon in the 1970s, with additional music recorded by the other band members in the 1990s. A machine learning algorithm was recently employed to separate Lennon’s vocals from his piano accompaniment, and this allowed a final version to be released.

But is it an authentic “Beatles” song? Not everyone is convinced.

Advances in technology have also allowed the manipulation of audio and video recordings. Referred to as “deepfakes,” such transformations can make it appear that a celebrity or a politician said something that they did not – a troubling prospect as the U.S. heads into what is sure to be a contentious 2024 election season.

Writing for The Conversation in May 2023, education scholar Victor R. Lee explored the AI-fueled authenticity crisis.

Our judgments of authenticity are knee-jerk, he explained, honed over years of experience. Sure, occasionally we’re fooled, but our antennae are generally reliable. Generative AI short-circuits this cognitive framework.

“That’s because back when it took a lot of time to produce original new content, there was a general assumption … that it only could have been made by skilled individuals putting in a lot of effort and acting with the best of intentions,” he wrote.

“These are not safe assumptions anymore,” he added. “If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, everyone will need to consider that it may not have actually hatched from an egg.”

Though there seems to be a general understanding that human minds and human hands must play some role in creating something authentic or being authentic, authenticity has always been a difficult concept to define.

So it’s somewhat fitting that as our collective handle on reality has become ever more tenuous, an elusive word for an abstract ideal is Merriam-Webster’s word of the year.![]()

Roger J. Kreuz, Associate Dean and Professor of Psychology, University of Memphis

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.