In the 1950s, scholars worried that, thanks to technological innovations, Americans wouldn’t know what to do with all of their leisure time.

Yet today, as sociologist Juliet Schor notes, Americans are overworked, putting in more hours than at any time since the Depression and more than in any other in Western society.

It’s probably not unrelated to the fact that instant and constant access has become de rigueur, and our devices constantly expose us to a barrage of colliding and clamoring messages: “Urgent,” “Breaking News,” “For immediate release,” “Answer needed ASAP.”

It disturbs our leisure time, our family time – even our consciousness.

Over the past decade, I’ve tried to understand the social and psychological effects of our growing interactions with new information and communication technologies, a topic I examine in my book “The Terminal Self: Everyday Life in Hypermodern Times.”

In this 24/7, “always on” age, the prospect of doing nothing might sound unrealistic and unreasonable.

But it’s never been more important.

Acceleration for the sake of acceleration

In an age of incredible advancements that can enhance our human potential and planetary health, why does daily life seem so overwhelming and anxiety-inducing?Why aren’t things easier?

It’s a complex question, but one way to explain this irrational state of affairs is something called the force of acceleration.

According to German critical theorist Hartmut Rosa, accelerated technological developments have driven the acceleration in the pace of change in social institutions.

We see this on factory floors, where “just-in-time” manufacturing demands maximum efficiency and the ability to nimbly respond to market forces, and in university classrooms, where computer software instructs teachers how to “move students quickly” through the material. Whether it’s in the grocery store or in the airport, procedures are implemented, for better or for worse, with one goal in mind: speed.

Noticeable acceleration began more than two centuries ago, during the Industrial Revolution. But this acceleration has itself … accelerated. Guided by neither logical objectives nor agreed-upon rationale, propelled by its own momentum, and encountering little resistance, acceleration seems to have begotten more acceleration, for the sake of acceleration.

To Rosa, this acceleration eerily mimics the criteria of a totalitarian power: 1) it exerts pressure on the wills and actions of subjects; 2) it is inescapable; 3) it is all-pervasive; and 4) it is hard or almost impossible to criticize and fight.

The oppression of speed

Unchecked acceleration has consequences.At the environmental level, it extracts resources from nature faster than they can replenish themselves and produces waste faster than it can be processed.

At the personal level, it distorts how we experience time and space. It deteriorates how we approach our everyday activities, deforms how we relate to each other and erodes a stable sense of self. It leads to burnout at one end of the continuum and to depression at the other. Cognitively, it inhibits sustained focus and critical evaluation. Physiologically, it can stress our bodies and disrupt vital functions.

When our environment accelerates, we must pedal faster in order to keep up with the pace. Workers receive more emails than ever before – a number that’s only expected to grow. The more emails you receive, the more time you need to process them. It requires that you either accomplish this or another task in less time, that you perform several tasks at once, or that you take less time in between reading and responding to emails.

American workers’ productivity has increased dramatically since 1973. What has also increased sharply during that same period is the pay gap between productivity and pay. While productivity between 1973 and 2016 has increased by 73.7 percent, hourly pay has increased by only 12.5 percent. In other words, productivity has increased at about six times the rate of hourly pay.

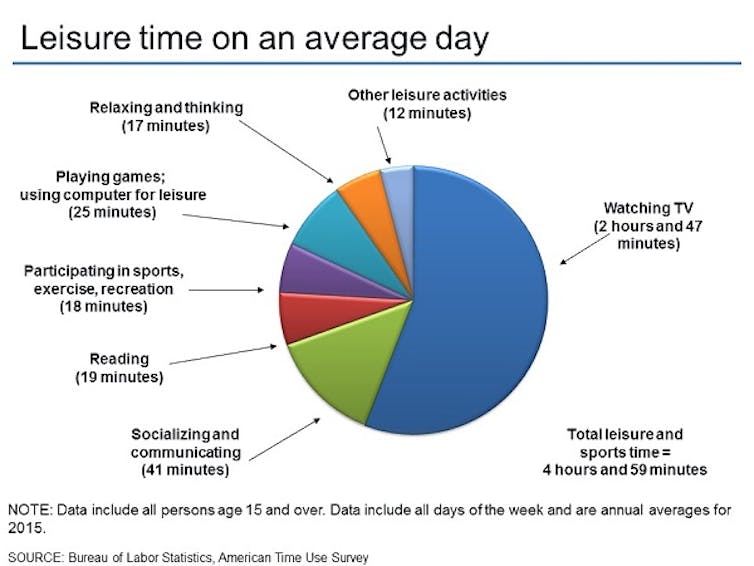

Clearly, acceleration demands more work – and to what end? There are only so many hours in a day, and this additional expenditure of energy reduces individuals’ ability to engage in life’s essential activities: family, leisure, community, citizenship, spiritual yearnings and self-development.

It’s a vicious loop: Acceleration imposes more stress on individuals and curtails their ability to manage its effects, thereby worsening it.

Doing nothing and ‘being’

In a hypermodern society propelled by the twin engines of acceleration and excess, doing nothing is equated with waste, laziness, lack of ambition, boredom or “down” time.

But this betrays a rather instrumental grasp of human existence.

Much research – and many spiritual and philosophical systems – suggest that detaching from daily concerns and spending time in simple reflection and contemplation are essential to health, sanity and personal growth.

Similarly, to equate “doing nothing” with nonproductivity betrays a short-sighted understanding of productivity. In fact, psychological research suggests that doing nothing is essential for creativity and innovation, and a person’s seeming inactivity might actually cultivate new insights, inventions or melodies.

As legends go, Isaac Newton grasped the law of gravity sitting under an apple tree. Archimedes discovered the law of buoyancy relaxing in his bathtub, while Albert Einstein was well-known for staring for hours into space in his office.

The academic sabbatical is centered on the understanding that the mind needs to rest and be allowed to explore in order to germinate new ideas.

Doing nothing – or just being – is as important to human well-being as doing something.

The key is to balance the two.

Taking your foot off the pedal

Since it will probably be difficult to go cold turkey from an accelerated pace of existence to doing nothing, one first step consists in decelerating. One relatively easy way to do so is to simply turn off all the technological devices that connect us to the internet – at least for a while – and assess what happens to us when we do.Danish researchers found that students who disconnected from Facebook for just one week reported notable increases in life satisfaction and positive emotions. In another experiment, neuroscientists who went on a nature trip reported enhanced cognitive performance.

Different social movements are addressing the problem of acceleration. The Slow Food movement, for example, is a grassroots campaign that advocates a form of deceleration by rejecting fast food and factory farming.

As we race along, it seems as though we’re not taking the time to seriously examine the rationale behind our frenetic lives – and mistakenly assume that those who are very busy must be involved in important projects.

Touted by the mass media and corporate culture, this credo of busyness contradicts both how most people in our society define “the good life” and the tenets of many Eastern philosophies that extol the virtue and power of stillness.

Simon Gottschalk, Professor of Sociology, University of Nevada, Las Vegas

This article was originally published on The Conversation.