Evidence is building around the world that elderly people are the most vulnerable group in the COVID-19 pandemic. They are more likely to develop severe symptoms and to die from this viral disease, especially if they have other medical conditions like heart disease or high blood pressure.

Globally, the death rate from COVID-19 increases most sharply for those aged 70 or higher. But this data comes primarily from high income countries with strong health care systems. In less developed countries, which have shorter life expectancies, high levels of pre-existing conditions known to worsen outcomes, and generally weaker health systems, mortality is likely to rise earlier.

The Gauteng City-Region Observatory, an independent research and analysis unit in Johannesburg, South Africa, conducts a survey every two years to measure people’s quality of life in the Gauteng city-region, the country’s economic centre. This mostly urban region has had the highest number of COVID-19 cases in South Africa so far. Because of the particularly high risk that the elderly face, we have used the data from the latest Quality of Life survey to understand more about their lives. This work forms part of the GCRO’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This picture of older people’s lives in Gauteng can inform welfare and health responses to the coronavirus pandemic. Decision makers need to understand the lives of the vulnerable, to ensure that policies provide appropriate protection and support.

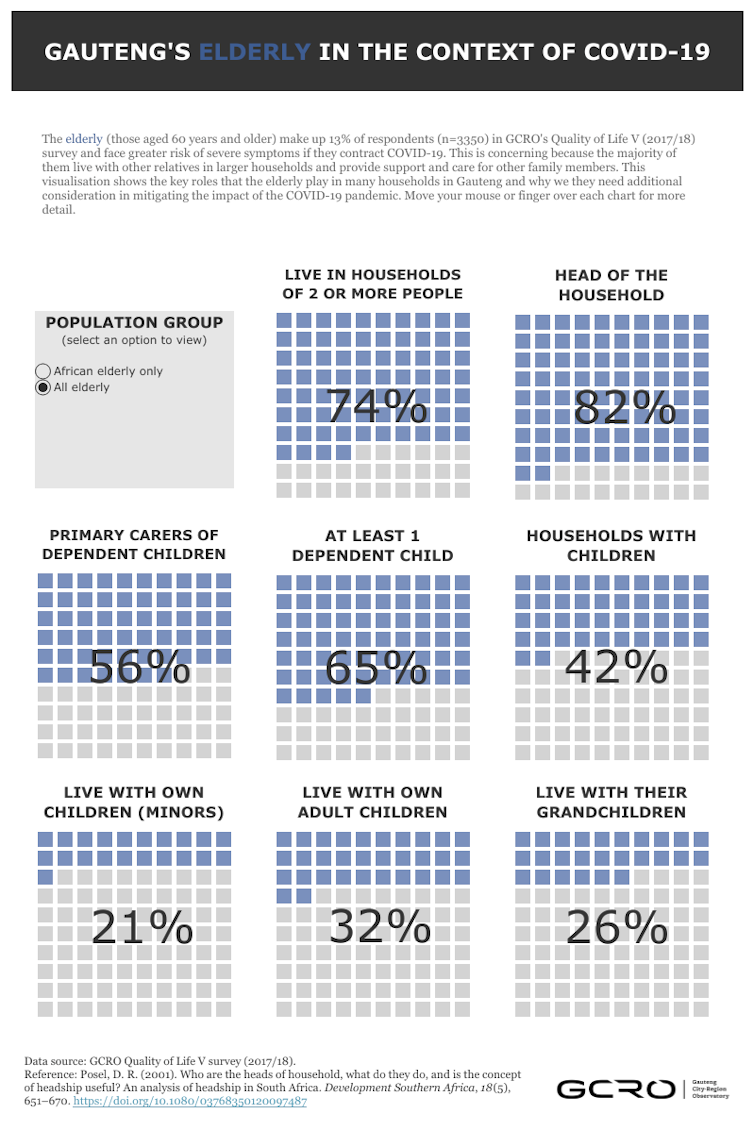

We looked at how the elderly form part of families and households, and fulfil important caregiving and economic roles. Our findings show that a very large proportion of people over the age of 60 identify themselves as head of the household. An equally high proportion identify themselves as the primary caregiver.

Our findings point to the fact that households headed by the elderly are likely to be particularly vulnerable in the COVID-19 pandemic.

A closer look at households in Gauteng province

South Africa’s apartheid history created substantially different population-age structures for different population groups. As household structure and the distribution of care-giving roles also vary by population group, we present separate data for African elders, for whom we have the largest sample size.We focused our analysis on those aged 60 and above – about 13% of all the 24,889 people in our Quality of Life survey.

Key results of our analysis can be explored in our interactive visualisation below.

Like South Africa as a whole, Gauteng has a high prevalence of medical conditions believed to worsen COVID-19 outcomes, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, TB and untreated HIV/AIDS. Life expectancy is already low (63.8 years for males and 69.2 years for females).

We found that most (74%) of the over-60s live in households of two or more people. Just 16% live only with their spouse. Their households are likely to contain several generations: 59% of the elderly live with family members other than their spouse, and 42% live in households with children under 18 years. Africans were even more likely (54%) to share the household with children.

The elderly frequently support children financially, including their own adult children. This is in part due to South Africa’s high unemployment rate and the fact that South Africans over 60 qualify for a social grant. Some 65% of elderly respondents (74% of African elderly) reported having at least one dependent child, and those with dependent children had an average of three.

Of elderly respondents who report having dependent children, 87% fulfil the role of primary carer. That makes up 56% of all elders.

As many as 85% of elderly respondents identify themselves as the head of their household and 48% of these are male.

What lockdown means for these households

With South Africa now under lockdown, the social and economic implications of the pandemic, and efforts to contain it, are becoming increasingly clear. Evidence of growing levels of hunger and income insecurity raises concerns about spiralling poverty, social unrest and economic collapse as a result of long term shutdowns.This has led some commentators to suggest that in countries like South Africa, there is a choice to be made between policies of lockdown, with wide economic and social impacts, and simply allowing the disease to run its course, which would increase deaths among the elderly. Others have convincingly highlighted the flaws in this argument and point to the social and economic costs of an overwhelmed health system and large numbers of deaths in a short period.

The relatively youthful population (South Africa’s median age is 25 and Gauteng’s is 29) may provide some protection against the impact of COVID-19. But the elderly do not exist in isolation from the rest of the population. Our analysis (consistent with national-level data) suggests that without intervention, this pandemic will have significant implications for many households that include the elderly, or rely on their support.

Even with intervention, the risks are substantial. South Africa’s current lockdown will inevitably need to be eased in coming weeks. Measures to protect the elderly and other at-risk groups, for example through “shielding”, must be considered. Understanding the location of the elderly – both physically and within families, households and communities – will be critical to establishing how to do this.

Household structure, along with population age distribution, is relevant to the risk of transmission. There is evidence that a large proportion of infections occur within households.

Our analysis highlights some of the difficulties of isolating the elderly in South Africa. It also shows that policies must take into account the financial and social support that the elderly provide.

The lives of Gauteng’s elderly are almost certainly intertwined with those of younger residents in numerous other ways beyond those presented here. Along with the pandemic’s economic and social costs, the human and emotional impacts of disrupted relationships between generations will be substantial.

Ways to support the elderly and their dependants

President Ramaphosa, in his address of Tuesday 21 April, announced several interventions to provide social and economic support. New interventions include expanded food assistance, temporary increases in social grant amounts, and temporary social distress grants for other unemployed individuals. If implemented rapidly and impartially, these interventions will relieve some pressure on the elderly and the households they support.But if the virus causes large numbers of hospitalisations and deaths, further support to the families of those affected will be needed. This may include continuing to pay out old age grants for six months after a beneficiary passes away, and psycho-social support to deal with illness and loss. Ongoing careful, data-driven and localised analysis of challenges and potential solutions will remain essential. The importance of protecting and supporting Gauteng’s elderly is clear.

Alexandra Parker, Researcher of urban & cultural studies, Gauteng City-Region Observatory and Julia de Kadt, Senior Researcher, Gauteng City-Region Observatory

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.