Claims of racial bias against black pupils at affluent private schools are becoming a routine South African event. They are also a symbol of the country’s reality.

The private schools were created by and for white people – this is reflected in their rules and customs. But they are seen as centres of education quality and so black people who can afford them send their children to them. But they either can’t or won’t change into institutions which include everyone. All of which is a fair description of South Africa since 1994.

In a just published book, Prisoners of the Past: South African Democracy and the Legacy of Minority Rule, I argue that the new order created when racial laws were scrapped in 1994 is “path dependent” – patterns which held sway in the old order are carried into the new. This does not mean that, as some claim, nothing has changed – anyone who claims there is no difference between racial minority rule and democracy was either not alive before 1994 or not paying attention. But core realities have not changed.

Before 1994, South Africa was divided into white insiders and black outsiders. Some who were outsiders are now insiders, the minority who have a regular income from the formal economy. But most remain outside. Within the insider group there are divisions: race is the most important.

Although racism is now outlawed, racial pecking orders survive – some black people have been absorbed into a still white-run economy, a reality confirmed by the make-up of boards and senior management. Middle class black people are among the angriest South Africans – they enjoy opportunities and hold qualifications which were unavailable to their parents, but experience many of the same racial attitudes. This fuels conflicts which sound like campaigns for radical economic change but are driven by middle-class anger at the survival of racial barriers.

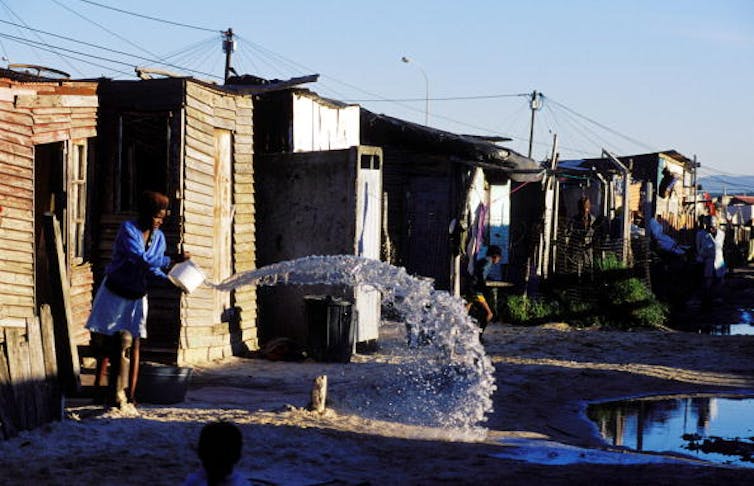

In the suburbs, people vote overwhelmingly for the opposition and hold the governing African National Congress (ANC) in contempt – in the townships and shack settlements where poor people live, the ANC still dominates although it has lost some ground. But the quality of public services in suburbs is still way above that in townships and authorities are much more likely to listen to suburbanites who pressure them. Under apartheid, too, the suburbs were well served and well heard, the townships were neither.

Wrong solutions

Why has democracy not ended these patterns? First, because the negotiations which ended minority rule tackled only the most obvious problem – that most South Africans were denied citizenship rights. No progress was possible without ending this, but it was only a part of what needed to change. There were no negotiated agreements on the economy or the professions or education.

In theory, changing the political system was meant to ensure that everything else changed too. But habits and hierarchies do not disappear simply because political rules change – neither does the balance of power in the economy and society. The political system is now controlled by the formerly excluded black majority – other areas of the country’s life are not.

Second, the political elite who took over in 1994 have not tried to change these realities because they – with, ironically, the old white economic and cultural elite – believe that the goal of democratic South Africa is to extend to everyone what whites enjoyed under apartheid. They have not built a new economic, cultural and social order – they have tried to slot as many black people as possible into what exists. The parents who send their children to suburban private schools and hope they will be treated with respect are following the same path.

Apartheid was good to whites. It gave them the vote and freedom of speech as long as they were not too sympathetic to blacks. It created large formal businesses and, in its heyday, whites were guaranteed a formal job. The suburbs of major cities resembled California in the US. It is this which the new and old elite want to extend to everyone.

Despite much talk of black economic empowerment, far more effort is devoted to the role of black people in the corporations which have dominated the economy for decades than to promoting black-owned businesses. In the professions, new black entrants have been expected to conform to the habits and rules created when whites controlled the society. Culturally, apartheid and its values may be discredited but the West remains the centre of attention.

Everyone can’t have what whites had under apartheid because there isn’t nearly enough of it to go around. While political rights can be enjoyed by everyone, apartheid’s economic and social benefits were what a fraction of the country enjoyed by using force to deny it to the rest. Once apartheid went, the living standards of the minority needed to adjust to what a middle income country could afford. Because they haven’t, there are just so many black people who can benefit.

It is common for the South African debate to blame the government, or particular people in it, for the country’s difficulties. But it is the realities described here which explain poor growth, continued inequality and the many problems of which the debate complains.

New thinking

It is easy to see why the white elites prefers the old arrangements – but why does the new black leadership want them? Anywhere one group dominates others, the standards and habits of the group in charge come to be seen as the measure of the good society: for the leadership of those at the wrong end of this, domination only ends when everyone shares in them. The response is very human – but it keeps alive the old order with its inequalities and unfairness.

Despite change in important areas this is the reality of post-1994 South Africa. It ensures that the country does not reach anything like its potential – that it is not only less humane than it might be but less well-off too because many are still barred from using their talents and energies to help it to grow.

South Africa is not, the book argues, doomed to follow this path forever. Change needs, firstly, new thinking, an approach which seeks a society which works for all its people. This is unlikely to come from elites, who are wedded to the present, but could be the product of campaigning by citizens. It could create the ground for negotiation which would tackle what the 1994 deal left untouched – how to create a new, shared, society and not only a new political order.

It is this path, not the constant search for the perfect political leader who will solve all problems, which could enable South Africa to bury its past and create a better future.![]()

Steven Friedman, Professor of Political Studies, University of Johannesburg

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.