Recent news stories have highlighted unethical and even lawless actions taken by people and corporations that were motivated primarily by greed.

Federal prosecutors, for example, charged 33 wealthy parents, some of whom were celebrities, with paying bribes to get their children into top colleges. In another case, lawyer Michael Avenatti was accused of trying to extort millions from Nike, the sports company.

Allegations of greed are listed in the lawsuit filed against members of Sackler family, the owners of Purdue Pharma, accused of pushing powerful painkillers as well as the treatment for addiction.

In all of these cases, individuals or companies seemingly had wealth and status to spare, yet they allegedly took actions to gain even further advantage. Why would such successful people or corporations allegedly commit crimes to get more?

As a scholar of comparative religious ethics, I frequently teach basic principles of moral thought in diverse religious traditions.

Religious thought can help us understand human nature and provide ethical guidance, including in cases of greed like the ones mentioned here.

Anxiety and injustice

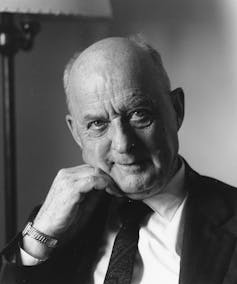

The work of the 20th-century theologian Reinhold Niebuhr on human anxiety offers one possible explanation for what might drive people to seek more than they already have or need.

Niebuhr was arguably the most famous theologian of his time. He was a mentor to several public figures. These included Arthur Schlesinger Jr., a historian who served in the Kennedy White House, and George F. Kennan, a diplomat and an adviser on Soviet affairs. Niebuhr also came to have a deep influence on former President Barack Obama.

Niebuhr said the human tendency to perpetuate injustice is the result of a deep sense of existential anxiety, which is part of the human condition. In his work “The Nature and Destiny of Man,” Niebuhr described human beings as creatures of both “spirit” and “nature.”

As “spirit,” human beings have consciousness, which allows them to rise above the sensory experiences they have in any given moment.

Yet, at the same time, he said, human beings do have physical bodies, senses and instincts, like any other animal. They are part of the natural world and are subject to the risks and vulnerabilities of mortality, including death.

Together, these traits mean that human beings are not just mortal, but also conscious of that mortality. This juxtaposition leads to a deeply felt anxiety, which, according to Niebuhr, is the “inevitable spiritual state of man.”

To deal with the anxiety of knowing they will die, Niebuhr says, human beings are tempted to – and often do – grasp at whatever means of security seem within their reach, such as knowledge, material goods or prestige.

In other words, people seek certainty in things that are inherently uncertain.

Hurting others

This is a fruitless task by definition, but the bigger problem is that the quest for certainty in one’s own life almost always harms others. As Niebuhr writes:“Man is, like the animals, involved in the necessities and contingencies of nature; but unlike the animals he sees this situation and anticipates its perils. He seeks to protect himself against nature’s contingencies; but he cannot do so without transgressing the limits which have been set for his life. Therefore all human life is involved in the sin of seeking security at the expense of other life.”The case of parents who may have committed fraud to gain coveted spots for their children at prestigious colleges offers an example of trying to find some of this certainty. That comes at the expense of others, who cannot gain admission to a college because another child has gotten in via illegitimate means.

As other research has shown, such anxiety may be more acute in those with higher social status. The fear of loss, among other things, could well drive such actions.

What we can learn from the Buddha

While Niebuhr’s analysis can help many of us understand the motivations behind greed, other religious traditions might offer further suggestions on how to deal with it.

Several centuries ago, the Buddha said that human beings have a tendency to attach themselves to “things” – sometimes material objects, sometimes “possessions” like prestige or reputation.

Scholar Damien Keown explains in his book on Buddhist ethics that in Buddhist thought, the whole universe is interconnected and ever-changing. People perceive material things as stable and permanent, and we desire and try to hold onto them.

But since loss is inevitable, our desire for things causes us to suffer. Our response to that suffering is often to grasp at things more and more tightly. But we end up harming others in our quest to make ourselves feel better.

Taken together, these thinkers provide insight into acts of greed committed by those who already have so much. At the same time, the teachings of the Buddha suggest that our most strenuous efforts to keep things for ourselves cannot overcome their impermanence. In the end, we will always lose what we are trying to grasp.

Laura E. Alexander, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies, Goldstein Family Community Chair in Human Rights, University of Nebraska Omaha

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.