With streets deserted, hospitals full and morgues struggling to cope with the number of bodies, it isn’t surprising that some people are making comparisons with the apocalypse.

The idea of an apocalypse, a time of catastrophic suffering, has existed for thousands of years.

Although things seemed bleak during ancient times of crisis, my research on ancient apocalypticism and its long history suggests that cultivating hope during times of chaos was essential.

Ancient apocalypticism

The word apocalypticism comes from the ancient Greek word “apokalypsis,” meaning a “revealing” or a “revelation.” Scholars define apocalypticism as a social and religious movement that sees the world in stark terms, such as dramatic visions that reveal a battle between good and evil and a coming judgment day.In more general terms, apocalypticism explained the cause of a crisis and how people should respond to it. The future, in most forms of apocalyptic thinking, meant imminent cataclysmic change: a new kingdom, a new world order.

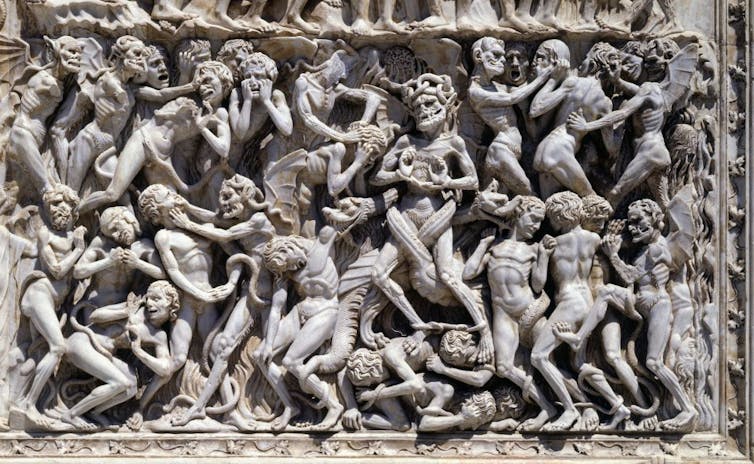

Apocalyptic ideas are an important theme in the Bible. The biblical Book of Revelation, for example, was written during a time of political upheaval when Christians were being persecuted.

Its dramatic visions included the “woman sitting on a scarlet beast…with seven heads and ten horns.” This vision, which probably alluded to the tyranny of imperial political authorities, was paradoxically a source of inspiration for early Christians, because it gave voice to their suffering.

But long before Revelation was written, apocalyptic thinking took root in ancient Judaism during times of significant political unrest, violent oppression and social devastation.

The Book of Daniel reflects one such crisis: Parts of this book were written in response to the conquests of Jerusalem by a Seleucid king named Antiochus Epiphanes. Antiochus desecrated the Jewish sacred temple in Jerusalem in the second century B.C. by setting up an altar to the God Zeus within the temple’s precincts.

The book addresses the suffering of the people, it recalls the history of violence and portrays this history with terrifying visions. But it also speaks of a coming judgment day that will be followed by a new kingdom – a kingdom that is everlasting and stands in contrast to the oppression of earlier times.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, dating to the period just after the apocalyptic writings in the Book of Daniel, spoke of impending terrible battles between good and evil.

Much of what scholars know about the Jewish community that wrote and preserved the Dead Sea Scrolls, speaks to a people in the throes of what appeared to be the end times.

The origins of Christianity lie in early Jewish apocalyptic worldviews: John the Baptist, Jesus, and the apostle Paul all seemed to have apocalyptic worldviews and preached messages about the imminent end times.

With its emphasis on a coming judgment day, one often accompanied by dramatic and destructive transformations, apocalypticism seems pessimistic. It certainly speaks to dire circumstances, as well as to fear and suffering.

Apocalyptic hope

But there is an important feature of apocalypticism that is often overlooked and it helps to explain why it continues to resurface throughout history and in our own times.

In powerful and important ways, apocalypticism was about hope. The ancient Greek word for hope – elpis – illuminates just how closely associated fear and hope were in the ancient world: Elpis referred to the anticipation or expectation of a good and safe future, but it could also refer to the fear of the unknown.

Apocalypticism cultivated a sense of meaning and encouragement through dire circumstances. It sought to make sense of suffering, and it predicted an end to suffering. In doing so, it gave people hope. Above all, apocalyptic thinking bonded people together in uncertain and challenging times.

Paul wrote that the judgment day will come “like a thief in the night” and he encouraged his followers to have “steadfastness of hope” in the midst of crisis. The Book of Revelation speaks repeatedly about “patient endurance” and it calls for love and faith during times of persecution and oppression.

The Book of Daniel writes poetically of those who “will shine like the brightness of the sky” in the time after the apocalypse. Other apocalyptic texts, such as the Sibylline Oracles, describe poetically a coming light, a “life without care,” and a time when the “earth will belong equally to all.”

It is this quality of hope and endurance that might be most important for our own time.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Kim Haines-Eitzen, Professor of Early Christianity, Cornell University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment