He survived the last great plague in London and the city’s Great Fire. He was imprisoned and persecuted for his religious and political views. There was no happy ending for the journalist Daniel Defoe, author of “A Journal of a Plague Year.” When he died in 1731, he was mired in debt and hiding from his creditors.

Yet Defoe, born in 1660, left behind a work of fiction that is one of the most widely published books in history and – other than the Bible – the most translated book in the world. Like many great works of fiction, it speaks across centuries, especially now as we face the COVID-19 pandemic.

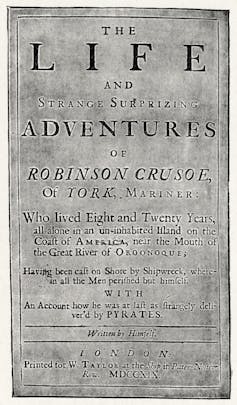

The book is “Robinson Crusoe,” written by Defoe and first published in 1719. Crusoe is an Englishman who leaves his comfortable life, goes to sea, gets captured by pirates and sold into slavery. Later, he emerges from a shipwreck the sole survivor. He sustains himself alone on a tropical island for 28 years, relying on grit, imagination and the few things he salvaged from the ship. His tale offers lessons for us all.

As a physician and scholar, I have taught Defoe’s novel many times to my students at Indiana University. I believe it is one of the best books to read as we endure the uncertainty and isolation due to COVID-19, because it invites us to reflect on existential issues at the core of a pandemic.

What matters in our lives?

For those hunkered down in the midst of a pandemic, one of Robinson Crusoe’s lessons is understanding the folly of worldly goods. Crusoe finds gold but realizes it is of no value to him, not even worth “taking off of the ground.” In his former life, money had become a “drug.” Now, marooned on an island, he learns what is truly necessary and rewarding in life.

Like Crusoe’s shipwreck, sheltering in place during COVID-19 interrupts long-established habits and rhythms of life. With this interruption comes a chance to examine our lives. What is genuinely necessary in life? And what things turn out to be little more than distractions? For example, where on such a spectrum would we situate the pursuit of wealth or caring well for loved ones?

Making do with very little

Crusoe quickly learns to be open to discovery. When he first arrives on the island, he finds it barren, inhospitable and threatening, like a prison. Over time, he comes to recognize it as home. As he explores the island and learns to live in harmony with it, it protects and sustains him. The island emerges as an unending source of wonder that at first he couldn’t see.

As my family and I have sheltered in place, we have shared a similar experience. We are taking more walks and lingering longer at the dinner table. Now that we are not rushing as much from one thing to another, we’ve discovered what it means to be in one place and simply savor being together.

Necessity, the mother of invention

Alone on an island, Crusoe can’t rely on anyone but himself to provide the things he needs. On the day of his shipwreck, he is naked, hungry and homeless. He laments that, “considered by his own nature,” man is “one of the most miserable creatures of the world.” Out of necessity, he figures out how to make the things he needs.

A pandemic renews opportunities for necessity to give birth to invention. Just as Crusoe finds within himself a resourcefulness he didn’t know he had, confinement can reveal new ways of living and creating. Even simple things such as cooking, reading, handcraft, writing and conversation may turn out to have more to offer than we supposed.

A wasted life and forgiveness

One of the greatest challenges Crusoe faces is unburdening himself of the guilt he bears for his misspent life. It had been devoted to getting rich and dominating other people – at the time of his shipwreck, he had been on a voyage to secure slaves for his plantation. But on the island, he begins to see the beauty in simple things. For example, he finds trees indescribably beautiful, a beauty so profound that it is “scarce credible.”

Something similar can transpire in the lives of the homebound. Frustration and disappointment can fade, to be replaced by new and unexpected sources of fulfillment. It may be something that we experience, such as a bird singing in the morning, but it can also be of our own doing. The tools lie at our fingertips – mail, phone and social media provide all we need to reach out to others with a kind word or helping hand.

Gratitude for what we have

One of the most profound transformations that Crusoe experiences is spiritual. Alone, he begins to meditate on the Bible he recovered from the shipwreck, reading Scripture three times per day. He attributes his newfound ability to “look on the bright side of my condition” to this habit, which gives him “such secret comforts that I cannot express them.”

By the time Crusoe is rescued after nearly three decades, he is a new man. He has formed the deepest friendship of his life with Friday, a man he rescued from death. He has learned the most profound lesson that “all our discontents about what we want spring from the want of thankfulness for what we have.”

A life of isolation

Enforced quiet and separation because of coronavirus can reacquaint some of us with the value of peace, while solitude can whet our appetites for the joys of true fellowship. Just as the shipwrecked Crusoe is reborn, so trying times can clarify for us the true bounties of our lives.

A pandemic can seem like the end, but it can also serve as a beginning. We are, in a way, cut adrift. Yet a new and ultimately more fertile landfall lies ahead, at least for those of us who are not sick, broke or homeless. If we heed Defoe’s inspiration, these unprecedented challenges can transform us into wiser and more caring human beings.

[You need to understand the coronavirus pandemic, and we can help. Read The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Richard Gunderman, Chancellor's Professor of Medicine, Liberal Arts, and Philanthropy, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

No comments:

Post a Comment