The South African government seems to have gone from an absence of data coupled to a firm but sensible strategy of lockdown to delay the pain of COVID-19, to a multitude of inputs and a seemingly cavalier attitude to the restrictions.

Statistics South Africa has submitted data on how the pandemic has devastated the country’s economy. Data from the Human Sciences Research Council points to overwhelming compliance with the restrictions by citizens, while regular updates by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases show the rates of infection continue to grow unabated.

Academics and NGOs have done the same, focusing primarily on the economy and poor people in particular. Many others have followed, with data or models or both.

In response, government developed a five-stage, evidence-informed strategy. This approach is meant to ease the lockdown, in place since 27 March, by assessing levels and sites of risk and adjusting accordingly. Government, and President Cyril Ramaphosa in particular, initially won global praise for their response to COVID-19 and apparent reliance on science to guide them. That was then.

Something has changed – the government or citizens?

Capriciousness

It is remarkable how quickly South Africans have lost the sense of camaraderie and support for a strong leader, and begun to complain rather about crypto-fascist authoritarianism. This was exacerbated by government as it introduced a “Stage 4” that was meant to be lighter than “Stage 5”.

It came with 73,000 more soldiers to help the police manage the new 8pm-5am curfew. So far, they have beaten up, threatened and intimidated innocent people, even killing a man. Citizens were permitted a “bonus” of three hours of exercise between 6am and 9am, making social distancing rather challenging.

On 1 May, when the relaxed restrictions kicked in, the roads were full of runners, walkers, shufflers, cyclists in their spandex, and dogs of every type. As he faced a sea of (mainly) white faces jogging on Cape Town’s Promenade, Police Minister Bheki Cele threatened:

I saw this thing of running, I think we will be making some form of recommendation to the National Command Council about it.

He added:

I saw … people running in clubs, walking with their dogs and they were even swimming – something that is [criminalised] in the regulations…

And in case anyone was in doubt about who had power, he added: “we can forget about Level 3” because such terrible behaviour meant citizens did not “deserve” it.

It is that final throw-away line that grates. This is not for citizens to “earn” or “deserve” because they behave well, it is meant to be a science-driven risk-based analysis that determines stages 1-5. But now it smacks of capriciousness, with more than a hint of pay-back.

Read more: South Africa's response to COVID-19 worsens the plight of waste reclaimers

South Africans – regardless of race or class – picked this up as they watched Cooperative Governance Minister Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma announce the reversal of a promise of tobacco sales being allowed under “Stage 4”, made earlier by President Ramaphosa. Similar to Cele telling them whether they “deserve” stage 3 or not.

Virtually all research into racial attitudes in South Africa has shown racial differentiation growing. This was most easily shown in the 2019 elections. These differences seem increasingly to be replaced by a shared hostility towards an ANC government that appears to be making rules up as they feel like it, and whose own ministers clearly feel above COVID-19 – and above citizens.

Throwback to an inglorious past

Are citizens protected by evidence-based interventions, or are they being jerked around by mean-spirited politicians?

If the country steps back, is there not something worth learning now, particularly for white South Africans?

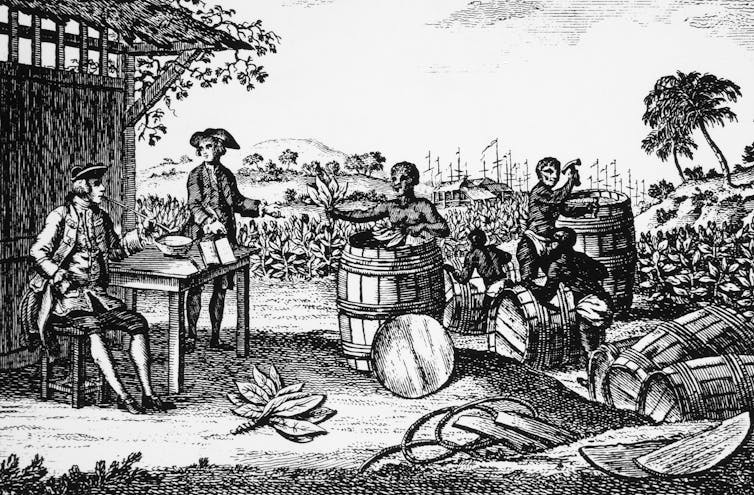

Think about it. You can’t go to work or school or to the park unless government says you can. Your freedom of movement is severely limited. You’re told when you’re allowed out, and you are supposed to have a permit akin to a dompas (dumb pass), to prove you’re legally out. (The dompas was the demeaning identity document all black people were required to carry during apartheid rule, which controlled their movements.)

Read more: South Africa needs to end the lockdown: here's a blueprint for its replacement

And the troops and police are there to ensure you obey, or beat the hell out of you. Your behaviours are deemed foreign, not normal. You can only enter certain shops, and only after you are sanitised (because you may be dirty or a vector of disease) and you can’t buy alcohol or cigarettes. And other than a small handful, your work is not essential and government will decide for you if you can work or not.

White South Africans right now have a rather comfortable, tiny insight into what life under apartheid was like. It can be a powerful moment to empathise with what it was like to be black under apartheid – and this time, blacks and whites are all being treated the same.

They are all irritated by a government that seems bent on exercising power in small, nasty ways. That’s why this can be a great moment, because black and white South Africans really are all in this together, and they all increasingly dislike their government together.

If white people can stop acting as if they are individually and personally being attacked, and understand the shared nature of both unhappiness and anger, there is real potential for some (much delayed) healing.

As the global economy tanks, whites with retirement policies and shares and businesses are being hit in the pocket. Society and the economy, they are told, are never going back to normal – they have to reset in different, as yet unknown ways.

Can they?

Never waste a good crisis

If South Africa has to reset, can its people – consciously and together – treat this as the real “miracle” moment? A lot of good work has been done since apartheid, which advantaged the white minority to the detriment of the black majority, ended in 1994. Millions of people now have clean water, water-borne sewerage, electricity, tarred roads, street lights and the like. Quite a few more have tertiary education, and some have wealth.

According to most studies, reconciliation has not fared well. Racism, racial redress and patronage have made short work of the noble goals of the early 1990s.

We should see the last 26 years as South Africans’ infrastructural investment for the real “new South Africa” to be able to emerge.

If we assume that the society matters more than simply repeating “it’s the economy, stupid!”, now is the chance to be different, and to reset to a new social reality. Wealth has been destroyed by COVID-19, and it has laid bare the lines of inequality for all to see. So, talk of a wealth tax sounds rational, not punitive, in the post-COVID-19 context.

Read more: Coronavirus: why South Africa needs a wealth tax now

South Africans can come out of lockdown as a more empathetic and united people – even if united in irritation or anger at a capricious government that seems to regard evidence-based decision-making as meaning regulations chop and change according to ministerial whim.

Can they use this moment to look beyond “race” and see a shared humanity?

It is rare that any post-authoritarian society gets two chances to reconcile. This may be just that, for white South Africans in particular.![]()

David Everatt, Professor, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.